National Standards for CLAS in Health and Health Care:

A Blueprint for Advancing and Sustaining CLAS Policy and Practice

National Standards for Culturally and Linguistically

Appropriate Services in Health and Health Care:

A Blueprint for Advancing and Sustaining CLAS

Policy and Practice

Office of Minority Health

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services

April 2013

National Standards for CLAS in Health and Health Care:

A Blueprint for Advancing and Sustaining CLAS Policy and Practice

i

Table of Contents

Acknowledgments ................................................................................................................. 7

Executive Summary ............................................................................................................... 8

National Standards for Culturally and Linguistically Appropriate Services in Health and Health Care .... 13

The Case for the Enhanced National CLAS Standards ........................................................... 14

Respond to Demographic Changes ..................................................................................................... 15

Eliminate Health Disparities ................................................................................................................ 16

Improve Quality of Services and Care ................................................................................................. 17

Meet Legislative, Regulatory, and Accreditation Mandates .................................................................. 17

Gain a Competitive Edge in the Market Place ...................................................................................... 19

Decrease the Risk of Liability .............................................................................................................. 19

The Enhanced National CLAS Standards .............................................................................. 21

The Standards .................................................................................................................................... 21

Purpose .............................................................................................................................................. 21

Audience ............................................................................................................................................ 21

Components of the Standards ............................................................................................................ 23

Strategies for Implementation ............................................................................................................ 23

Enhancements to the National CLAS Standards ................................................................... 24

Culture ............................................................................................................................................... 24

Health ................................................................................................................................................ 27

Health and Health Care Organizations ................................................................................................ 27

Individuals and Groups ....................................................................................................................... 28

Statement of Intent ............................................................................................................................ 28

Clarity and Action ............................................................................................................................... 29

Standards of Equal Importance .......................................................................................................... 29

Principal Standard and Three Enhanced Themes ................................................................................ 30

New Standard: Organizational Governance and Leadership................................................................. 33

National Standards for CLAS in Health and Health Care:

A Blueprint for Advancing and Sustaining CLAS Policy and Practice

ii

Looking Ahead: The Future and the National CLAS Standards.............................................. 34

Continued Enhancements ................................................................................................................... 34

State and Federal Legislation .............................................................................................................. 34

Support and Guidance ........................................................................................................................ 34

Bibliography ........................................................................................................................ 36

The Blueprint ...................................................................................................................... 43

Standard 1: Provide Effective, Equitable, Understandable, and Respectful Quality Care and

Services .............................................................................................................................. 44

Standard 1 ......................................................................................................................................... 44

Purpose .............................................................................................................................................. 44

Components of the Standard .............................................................................................................. 44

Strategies for Achievement of the Principal Standard .......................................................................... 48

Resources .......................................................................................................................................... 48

Bibliography ....................................................................................................................................... 49

Standard 2: Advance and Sustain Governance and Leadership that Promotes CLAS and

Health Equity ...................................................................................................................... 52

Standard 2 ......................................................................................................................................... 52

Purpose .............................................................................................................................................. 52

Components of the Standard .............................................................................................................. 52

Strategies for Implementation ............................................................................................................ 56

Resources .......................................................................................................................................... 57

Bibliography ....................................................................................................................................... 58

Standard 3: Recruit, Promote, and Support a Diverse Governance, Leadership, and Workforce

........................................................................................................................................... 60

Standard 3 ......................................................................................................................................... 60

Purpose .............................................................................................................................................. 60

Components of the Standard .............................................................................................................. 60

Strategies for Implementation ............................................................................................................ 62

Resources .......................................................................................................................................... 63

National Standards for CLAS in Health and Health Care:

A Blueprint for Advancing and Sustaining CLAS Policy and Practice

iii

Bibliography ....................................................................................................................................... 64

Standard 4: Educate and Train Governance, Leadership, and Workforce in CLAS ................. 66

Standard 4 ......................................................................................................................................... 66

Purpose .............................................................................................................................................. 66

Components of the Standard .............................................................................................................. 66

Strategies for Implementation ............................................................................................................ 68

Resources .......................................................................................................................................... 69

Bibliography ....................................................................................................................................... 70

Standard 5: Offer Communication and Language Assistance ............................................... 72

Standard 5 ......................................................................................................................................... 72

Purpose .............................................................................................................................................. 72

Components of the Standard .............................................................................................................. 72

Strategies for Implementation ............................................................................................................ 76

Resources .......................................................................................................................................... 76

Bibliography ....................................................................................................................................... 77

Standard 6: Inform Individuals of the Availability of Language Assistance .......................... 79

Standard 6 ......................................................................................................................................... 79

Purpose .............................................................................................................................................. 79

Components of the Standard .............................................................................................................. 79

Strategies for Implementation ............................................................................................................ 81

Resources .......................................................................................................................................... 83

Bibliography ....................................................................................................................................... 83

Standard 7: Ensure the Competence of Individuals Providing Language Assistance ............ 85

Standard 7 ......................................................................................................................................... 85

Purpose .............................................................................................................................................. 85

Components of the Standard .............................................................................................................. 85

Strategies for Implementation ............................................................................................................ 88

Resources .......................................................................................................................................... 89

National Standards for CLAS in Health and Health Care:

A Blueprint for Advancing and Sustaining CLAS Policy and Practice

iv

Bibliography ....................................................................................................................................... 90

Standard 8: Provide Easy-to-Understand Materials and Signage ......................................... 93

Standard 8 ......................................................................................................................................... 93

Purpose .............................................................................................................................................. 93

Components of the Standard .............................................................................................................. 93

Strategies for Implementation ............................................................................................................ 95

Resources .......................................................................................................................................... 96

Bibliography ....................................................................................................................................... 97

Standard 9: Infuse CLAS Goals, Policies, and Management Accountability Throughout the

Organization’s Planning and Operations .............................................................................. 99

Standard 9 ......................................................................................................................................... 99

Purpose .............................................................................................................................................. 99

Components of the Standard .............................................................................................................. 99

Strategies for Implementation .......................................................................................................... 100

Resources ........................................................................................................................................ 101

Bibliography ..................................................................................................................................... 102

Standard 10: Conduct Organizational Assessments ........................................................... 103

Standard 10 ..................................................................................................................................... 103

Purpose ............................................................................................................................................ 103

Components of the Standard ............................................................................................................ 103

Strategies for Implementation .......................................................................................................... 105

Resources ........................................................................................................................................ 106

Bibliography ..................................................................................................................................... 107

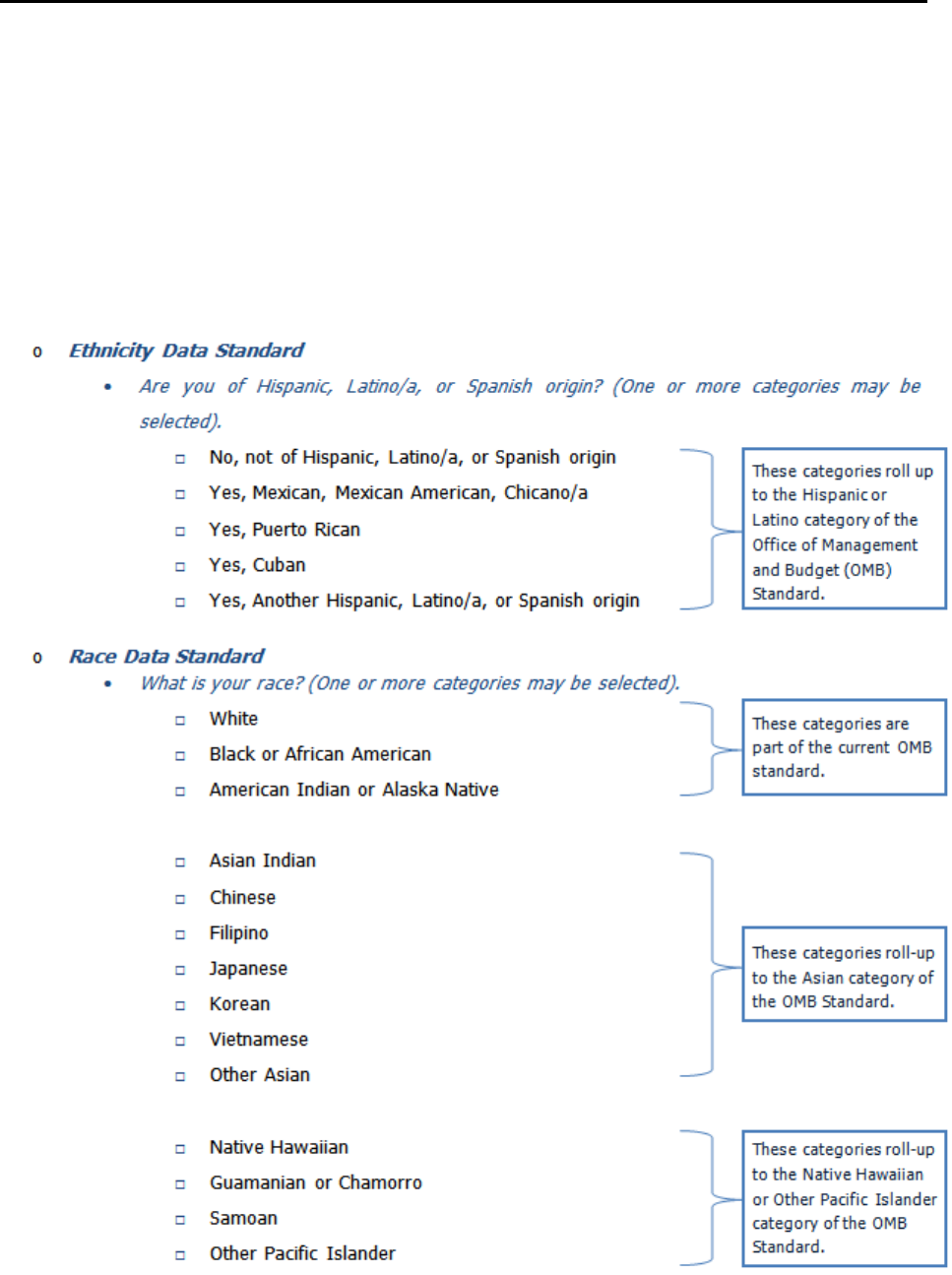

Standard 11: Collect and Maintain Demographic Data ....................................................... 108

Standard 11 ..................................................................................................................................... 108

Purpose ............................................................................................................................................ 108

Components of the Standard ............................................................................................................ 108

Strategies for Implementation .......................................................................................................... 113

National Standards for CLAS in Health and Health Care:

A Blueprint for Advancing and Sustaining CLAS Policy and Practice

v

Resources ........................................................................................................................................ 115

Bibliography ..................................................................................................................................... 116

Standard 12: Conduct Assessments of Community Health Assets and Needs ..................... 118

Standard 12 ..................................................................................................................................... 118

Purpose ............................................................................................................................................ 118

Components of the Standard ............................................................................................................ 118

Strategies for Implementation .......................................................................................................... 120

Resources ........................................................................................................................................ 122

Bibliography ..................................................................................................................................... 122

Standard 13: Partner with the Community ........................................................................ 124

Standard 13 ..................................................................................................................................... 124

Purpose ............................................................................................................................................ 124

Components of the Standard ............................................................................................................ 124

Strategies for Implementation .......................................................................................................... 125

Resources ........................................................................................................................................ 126

Bibliography ..................................................................................................................................... 127

Standard 14: Create Conflict and Grievance Resolution Processes ..................................... 129

Standard 14 ..................................................................................................................................... 129

Purpose ............................................................................................................................................ 129

Components of the Standard ............................................................................................................ 129

Strategies for Implementation .......................................................................................................... 130

Resources ........................................................................................................................................ 131

Bibliography ..................................................................................................................................... 132

Standard 15: Communicate the Organization’s Progress in Implementing and Sustaining

CLAS ................................................................................................................................. 133

Standard 15 ..................................................................................................................................... 133

Purpose ............................................................................................................................................ 133

Components of the Standard ............................................................................................................ 133

National Standards for CLAS in Health and Health Care:

A Blueprint for Advancing and Sustaining CLAS Policy and Practice

vi

Strategies for Implementation .......................................................................................................... 134

Resources ........................................................................................................................................ 135

Bibliography ..................................................................................................................................... 136

Appendix A: Glossary ........................................................................................................ 137

Bibliography ..................................................................................................................................... 148

Appendix B: National CLAS Standards Enhancement Initiative .......................................... 155

Background ...................................................................................................................................... 155

Goals ................................................................................................................................................ 155

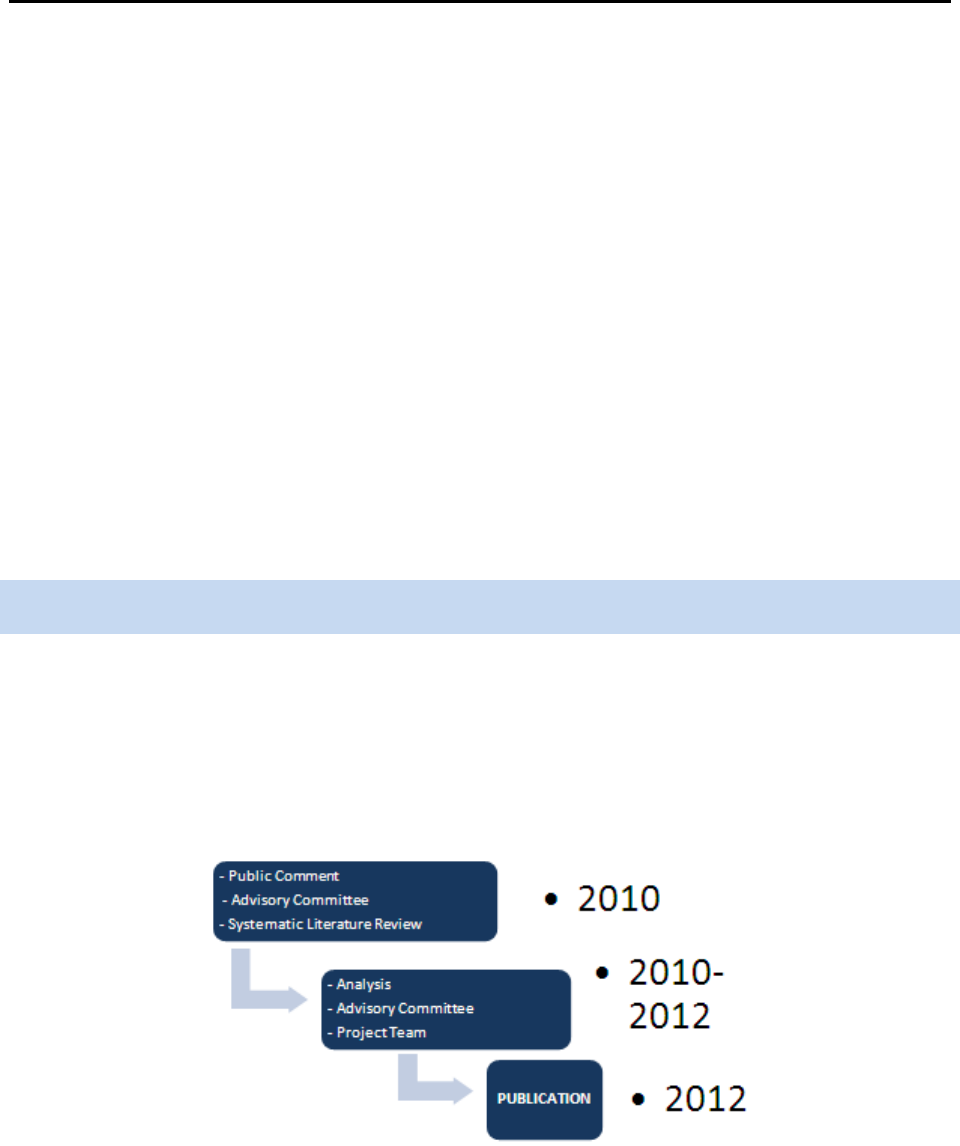

Development Process ....................................................................................................................... 156

Public Comment ............................................................................................................................... 157

National Project Advisory Committee ................................................................................................ 158

Appendix C: National Project Advisory Committee ............................................................ 162

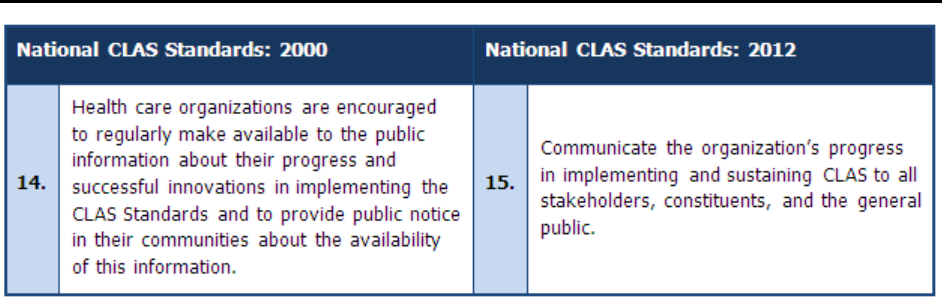

Appendix D: Crosswalk – National CLAS Standards 2000 and 2012 ................................... 165

Appendix E: Resources ...................................................................................................... 169

List of Figures and Tables

Figure 1: State Legislation...................................................................................................................... 18

Figure 2: Interrelationship of Aspects of Culture..................................................................................... 27

Figure 3: Enhanced National CLAS Standards’ Themes ........................................................................... 31

Figure 4: Phases of the National CLAS Standards Enhancement Initiative ............................................. 156

Figure 5: Advisory Committee Meetings ............................................................................................... 159

Table 1: Blueprint Chapter Structure ...................................................................................................... 43

Table 2: Examples of Promoting CLAS Through Policy and Practice ........................................................ 54

Table 3: Interpreting and Translating ..................................................................................................... 73

Table 4: A Process for Collecting Data .................................................................................................. 114

National Standards for CLAS in Health and Health Care:

A Blueprint for Advancing and Sustaining CLAS Policy and Practice

Acknowledgments 7

Acknowledgments

This document is the result of a multiyear process that involved many individuals across the country. We

extend our appreciation to them:

o The National Project Advisory Committee (Advisory Committee) members, for their generosity in

sharing their time and expertise and their tireless dedication in the review of numerous drafts of

terminology, documents, and the enhanced National CLAS Standards. A complete list of the

Advisory Committee members appears in Appendix C.

o The individuals and organizations who participated in the public comment period, either by

attending a public comment meeting or by providing online or written submissions. Your input

helped to inform the enhancements to the National CLAS Standards, originally released in 2000.

National Standards for CLAS in Health and Health Care:

A Blueprint for Advancing and Sustaining CLAS Policy and Practice

Executive Summary 8

Executive Summary

Health equity is the attainment of the highest level of health for all people (U.S. Department of Health

and Human Services [HHS] Office of Minority Health [OMH], 2011). Currently, individuals across the

United States from various cultural backgrounds are unable to attain their highest level of health for

several reasons, including the social determinants of health, or those conditions in which individuals are

born, grow, live, work, and age (World Health Organization [WHO], 2012), such as socioeconomic status,

education level, and the availability of health services (HHS Office of Disease Prevention and Health

Promotion [ODPHP], 2010a). Though health inequities are directly related to the existence of historical

and current discrimination and social injustice, one of the most modifiable factors is the lack of culturally

and linguistically appropriate services, broadly defined as care and services that are respectful of and

responsive to the cultural and linguistic needs of all individuals.

Health inequities result in disparities that directly affect the quality of life for all individuals. Health

disparities adversely affect neighborhoods, communities, and the broader society, thus making the issue

not only an individual concern but also a public health concern. In the United States, it has been

estimated that the combined cost of health disparities and subsequent deaths due to inadequate and/or

inequitable care is $1.24 trillion (LaVeist, Gaskin, & Richard, 2009). Culturally and linguistically

appropriate services are increasingly recognized as effective in improving the quality of care and services

(Beach et al., 2004; Goode, Dunne, & Bronheim, 2006). There are numerous ethical and practical reasons

why providing culturally and linguistically appropriate services in health and health care is necessary,

including the following, which have been identified by the National Center for Cultural Competence

(Cohen & Goode, 1999, revised by Goode & Dunne, 2003):

1. To respond to current and projected demographic changes in the United States.

2. To eliminate long-standing disparities in the health status of people of diverse racial, ethnic

and cultural backgrounds.

3. To improve the quality of services and primary care outcomes.

4. To meet legislative, regulatory and accreditation mandates.

5. To gain a competitive edge in the market place.

6. To decrease the likelihood of liability/malpractice claims.

The six reasons for the implementation of cultural competency as described by the National Center for

Cultural Competence fall into two frequently cited overarching philosophies: one that pertains to social

justice and the other that pertains to standards of business. The social justice philosophy emphasizes

diversity and the improvement of services to underserved populations, while the standards of business

philosophy focuses on strengthening business practices and business development.

National Standards for CLAS in Health and Health Care:

A Blueprint for Advancing and Sustaining CLAS Policy and Practice

Executive Summary 9

The enhanced National Standards for Culturally and Linguistically Appropriate Services (CLAS) in Health

and Health Care, known as the enhanced National CLAS Standards, from the Office of Minority Health at

the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services are intended to advance health equity, improve

quality, and help eliminate health care disparities by providing a blueprint for individuals and health and

health care organizations to implement culturally and linguistically appropriate services. The enhanced

National CLAS Standards align with the HHS Action Plan to Reduce Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities

(HHS, 2011) and the National Stakeholder Strategy for Achieving Health Equity (National Partnership for

Action to End Health Disparities, 2011a), which aim to promote health equity through providing clear

plans and strategies to guide collaborative efforts that address racial and ethnic health disparities across

the country. Adoption of these Standards will help advance better health and health care in the United

States.

The enhanced National CLAS Standards are built upon the groundwork laid by the original National CLAS

Standards, developed in 2000 by the HHS Office of Minority Health. The original National CLAS Standards

provided guidance on cultural and linguistic competency, with the ultimate goal of reducing racial and

ethnic health care disparities. Over the past decade, the original National CLAS Standards have served as

catalyst and conduit for efforts to improve the quality of care and achieve health equity (e.g., Diamond,

Wilson-Stronks, & Jacobs, 2010; Joint Commission, 2010; Kairys & Like, 2006).

The HHS Office of Minority Health undertook the National CLAS Standards Enhancement Initiative from

2010 to 2012 to recognize the nation’s increasing diversity, to reflect the tremendous growth in the fields

of cultural and linguistic competency over the past decade, and to ensure relevance with new national

policies and legislation, such as the Affordable Care Act. A decade after the publication of the original

National CLAS Standards, there is still much work to be done. Racial and ethnic disparities in health and

health care remain a significant public health issue, despite advances in health care technology and

delivery, even when factors such as insurance coverage, income, and educational attainment are taken

into account (American College of Physicians, 2010; Griffith, Yonas, Mason, & Havens, 2010). Cultural

and linguistic competency strives to improve the quality of care received and to reduce disparities

experienced by racial and ethnic minorities and other underserved populations (Saha, Beach, & Cooper,

2008). Through the National CLAS Standards Enhancement Initiative, a new benchmark is being

established for culturally and linguistically appropriate services to improve the health of all individuals.

The National CLAS Standards Enhancement Initiative’s development process, described in detail in

Appendix B, was informed by three primary sources: public comment, a National Project Advisory

Committee, and a systematic literature review. These three sources of data informed the scope and

direction of the Enhancement Initiative, and, ultimately, the enhanced National CLAS Standards. For

example, the majority of public comments indicated that while the original National CLAS Standards met

the intended needs as a whole, additional context was needed regarding the Standards’ focus and

National Standards for CLAS in Health and Health Care:

A Blueprint for Advancing and Sustaining CLAS Policy and Practice

Executive Summary 10

purpose, as well as more clearly defined key terminology. Additional comments suggested that the

organizations targeted for implementing the National CLAS Standards should be expanded and that

additional guidance regarding implementation should be provided.

The data collected from public comment, the National Project Advisory Committee, and the systematic

literature review showed strong support for expanding the key concepts of culture and health, which

serve as the conceptual underpinnings of the National CLAS Standards. Adopting a more comprehensive

conceptualization of health requires, by extension, a more inclusive recognition of the variety of

professionals and organizations providing the related care and services. The enhancements related to this

are as follows:

o

Culture

is defined as the integrated pattern of thoughts, communications, actions, customs,

beliefs, values, and institutions associated, wholly or partially, with racial, ethnic, or linguistic

groups, as well as with religious, spiritual, biological, geographical, or sociological characteristics.

Culture is dynamic in nature, and individuals may identify with multiple cultures over the course

of their lifetimes. This definition is adapted from other widely accepted definitions of culture (i.e.,

Gilbert, Goode, & Dunne, 2007; HHS OMH, 2005) and attempts to reflect the complex nature of

culture, as well as the various ways in which culture has been defined and studied across

multiple disciplines.

o

Health

is understood to encompass many aspects, including physical, mental, social, and

spiritual well-being (HHS Indian Health Services [IHS], n.d.; HHS Office of the Surgeon General

[OSG] & National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention, 2012; WHO, 1946). The World Health

Organization also notes that health is “not merely the absence of disease or infirmity” (WHO,

1946). Health status occurs along a continuum and therefore can range from poor to excellent.

The advancement of health equity allows individuals to experience better health over the course

of their life spans.

o

Audience

The enhanced National CLAS Standards reference both health and health care

organizations to acknowledge those working not only in health care settings, such as hospitals,

clinics, and community health centers, but also in organizations that provide services such as

behavioral and mental health, public health, emergency services, and community health. Any

organization addressing individual or community health, health care, or well-being can benefit

from the adoption and implementation of the National CLAS Standards.

To further reflect the more inclusive nature of the enhanced National CLAS Standards, the

enhanced Standards use the terminology

individuals and groups

in lieu of

patients

and

consumers

.

Individuals and groups

encompass patients, consumers, clients, recipients, families,

National Standards for CLAS in Health and Health Care:

A Blueprint for Advancing and Sustaining CLAS Policy and Practice

Executive Summary 11

caregivers, and communities. Therefore, the term

individuals and groups

includes anyone

receiving services from a health or health care organization.

Thus, the enhanced National CLAS Standards incorporate broader definitions of culture and health and

aim to reach a broader audience, in an effort to ensure that every individual has the opportunity to

receive culturally and linguistically appropriate health care and services.

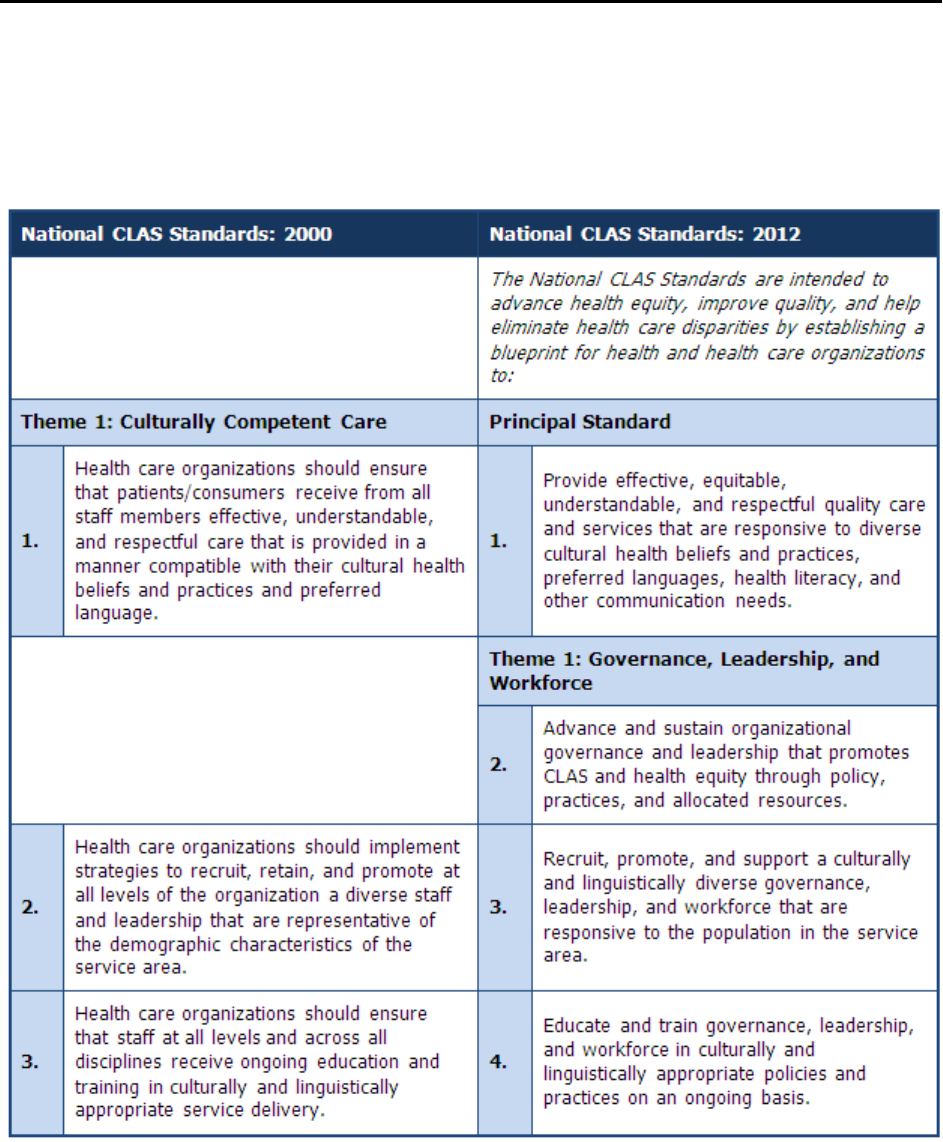

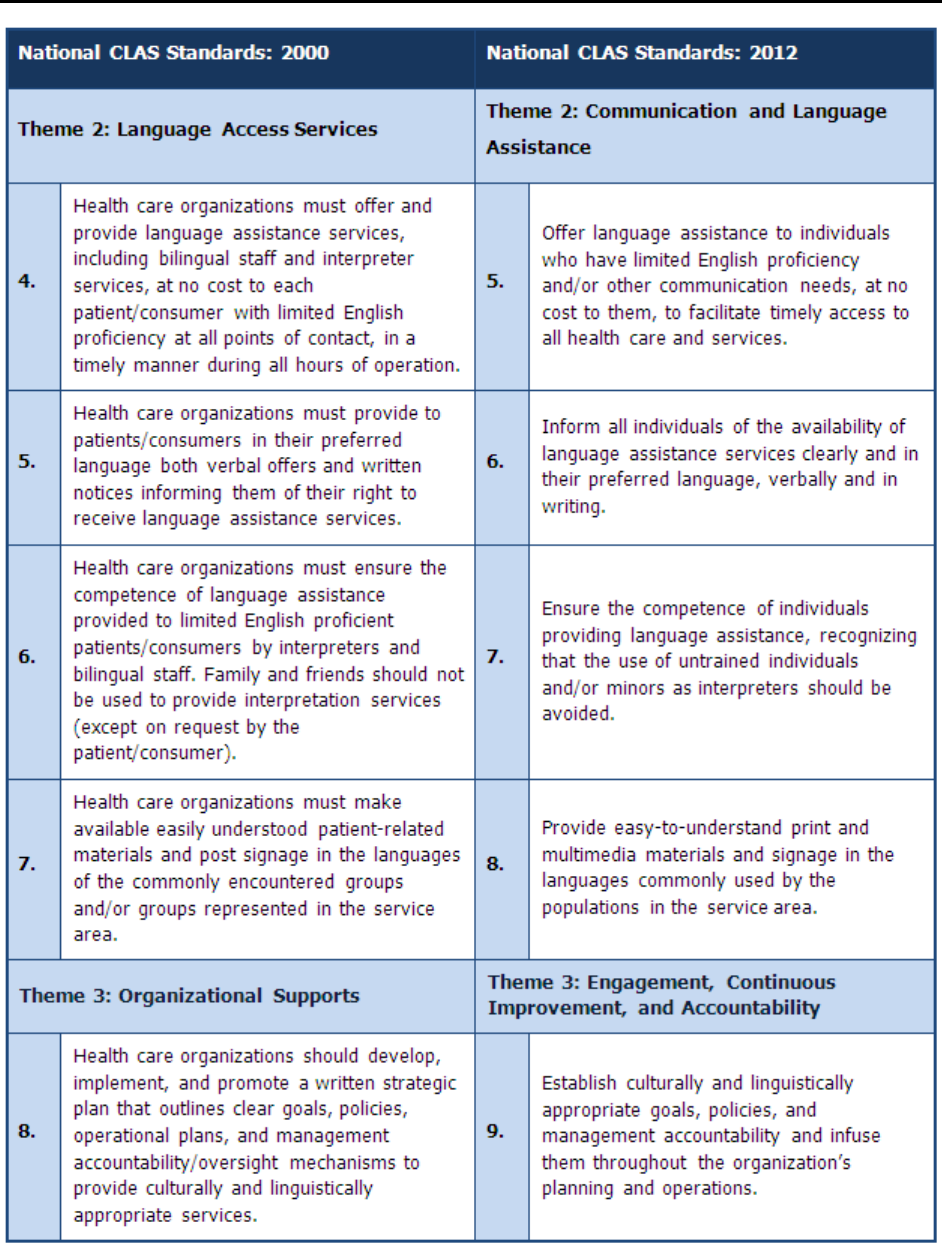

The data collected from public comment, the National Project Advisory Committee, and the systematic

literature review also informed several enhancements to the structure and content of the National CLAS

Standards, as follows (see Appendix D for a comparison between the original and enhanced National

CLAS Standards):

o

Statement of Intent:

The enhanced National CLAS Standards include an introductory

statement:

“The National CLAS Standards are intended to advance health equity, improve quality, and help

eliminate health care disparities by establishing a blueprint for health and health care

organizations to:”

The addition of the statement of intent ties the culturally and linguistically competent policies and

practices posed in the enhanced National CLAS Standards directly to the goals of advancing

health equity, improving quality, and eliminating health care disparities.

o

Clarity and Action:

Each of the National CLAS Standards was revised for greater clarity and

focus. In addition, the wording of each of the 15 Standards now begins with an action word to

emphasize how the desired goal may be achieved.

o

Standards of Equal Importance:

The original National CLAS Standards designated each

Standard as a recommendation, mandate, or guideline. The enhanced National CLAS Standards,

however, promote collective adoption of all Standards to promote optimal health and well-being

of all individuals. Each of the 15 Standards should be viewed as an equally important guideline to

advance health equity, improve quality, and help eliminate health care disparities.

o

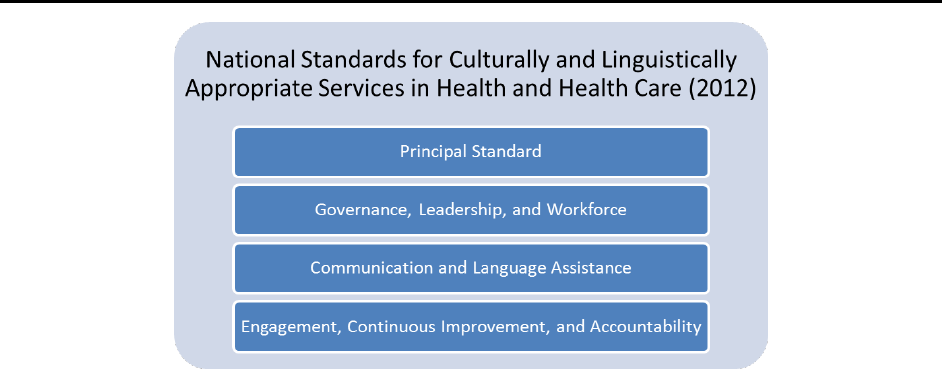

Principal Standard and Three Enhanced Themes:

The enhanced Standards have been

reorganized to address feedback obtained from the Enhancement Initiative and to improve their

overall intention, clarity, and practicality. The enhanced National CLAS Standards elevate the

previous Standard 1 to the status of Principal Standard and reframe the three themes. The

names of the three themes have been updated both to clarify intent and to broaden the scope of

their interpretation and application.

•

Principal Standard:

Standard 1 has been made the Principal Standard with the

understanding that it frames the essential goal of all of the Standards, and if the other 14

National Standards for CLAS in Health and Health Care:

A Blueprint for Advancing and Sustaining CLAS Policy and Practice

Executive Summary 12

Standards are adopted, implemented, and maintained, then the Principal Standard will be

achieved.

•

Theme 1:

Governance, Leadership, and Workforce — Changing the name of Theme 1

from Culturally Competent Care to Governance, Leadership, and Workforce provides

greater clarity on the specific locus of action for each of these Standards and emphasizes

the importance of CLAS implementation as a systemic responsibility, requiring the

endorsement and investment of leadership, and the support and training of all individuals

within an organization.

•

Theme 2:

Communication and Language Assistance — Changing the name of Theme 2

from Language Access Services to Communication and Language Assistance broadens

the understanding and application of appropriate services to include all communication

needs and services, e.g., sign language, braille, oral interpretation, and written

translation.

• Theme 3: Engagement, Continuous Improvement, and Accountability — Changing the

name of Theme 3 from Organizational Supports to Engagement, Continuous

Improvement, and Accountability underscores the importance of establishing individual

responsibility for ensuring that CLAS is supported, while maintaining that effective

delivery of CLAS demands action across organizations.

o

New Standard: Organizational Governance and Leadership:

The enhanced National CLAS

Standards emphasize the importance of CLAS being integrated throughout an organization. This

requires a bottom-up and a top-down approach to advancing and sustaining CLAS. Organizational

governance and leadership are key to ensuring the successful implementation and maintenance

of CLAS. In recognition of this, the enhanced National CLAS Standards include a new Standard

focused on the role of governance and leadership as it relates to CLAS. A complete list of all 15

enhanced National CLAS Standards, including the new Standard, can be found at the end of this

executive summary.

This document, the

National Standards for Culturally and Linguistically Appropriate Services in Health and

Health Care: A Blueprint for Advancing and Sustaining CLAS Policy and Practice

(

The Blueprint)

, offers a

user-friendly format for providing comprehensive — but by no means exhaustive — information on each

Standard.

The Blueprint

is an implementation guide for advancing and sustaining culturally and

linguistically appropriate services within health and health care organizations.

The Blueprint

dedicates one

chapter to each of the 15 Standards. These chapters review the Standard’s purpose, components, and

strategies for implementation. In addition, each chapter provides a list of resources that provide

additional information and guidance on that Standard.

National Standards for CLAS in Health and Health Care:

A Blueprint for Advancing and Sustaining CLAS Policy and Practice

Executive Summary 13

National Standards for Culturally and Linguistically Appropriate

Services in Health and Health Care

The National CLAS Standards are intended to advance health equity, improve quality, and help eliminate

health care disparities by establishing a blueprint for health and health care organizations to:

Principal Standard:

1. Provide effective, equitable, understandable, and respectful quality care and services that are

responsive to diverse cultural health beliefs and practices, preferred languages, health literacy,

and other communication needs.

Governance, Leadership, and Workforce:

2. Advance and sustain organizational governance and leadership that promotes CLAS and health

equity through policy, practices, and allocated resources.

3. Recruit, promote, and support a culturally and linguistically diverse governance, leadership, and

workforce that are responsive to the population in the service area.

4. Educate and train governance, leadership, and workforce in culturally and linguistically

appropriate policies and practices on an ongoing basis.

Communication and Language Assistance:

5. Offer language assistance to individuals who have limited English proficiency and/or other

communication needs, at no cost to them, to facilitate timely access to all health care and

services.

6. Inform all individuals of the availability of language assistance services clearly and in their

preferred language, verbally and in writing.

7. Ensure the competence of individuals providing language assistance, recognizing that the use of

untrained individuals and/or minors as interpreters should be avoided.

8. Provide easy-to-understand print and multimedia materials and signage in the languages

commonly used by the populations in the service area.

Engagement, Continuous Improvement, and Accountability:

9. Establish culturally and linguistically appropriate goals, policies, and management accountability,

and infuse them throughout the organization’s planning and operations.

10. Conduct ongoing assessments of the organization’s CLAS-related activities and integrate CLAS-

related measures into measurement and continuous quality improvement activities.

11. Collect and maintain accurate and reliable demographic data to monitor and evaluate the impact

of CLAS on health equity and outcomes and to inform service delivery.

12. Conduct regular assessments of community health assets and needs and use the results to plan

and implement services that respond to the cultural and linguistic diversity of populations in the

service area.

13. Partner with the community to design, implement, and evaluate policies, practices, and services

to ensure cultural and linguistic appropriateness.

14. Create conflict and grievance resolution processes that are culturally and linguistically appropriate

to identify, prevent, and resolve conflicts or complaints.

15. Communicate the organization’s progress in implementing and sustaining CLAS to all

stakeholders, constituents, and the general public.

National Standards for CLAS in Health and Health Care:

A Blueprint for Advancing and Sustaining CLAS Policy and Practice

The Case for the Enhanced National CLAS Standards 14

The Case for the Enhanced National CLAS Standards

Of all the forms of inequality, injustice in health care is the most shocking and inhumane.

— Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

Health equity is the attainment of the highest level of health for all people (HHS OMH, 2011). Currently,

individuals across the United States from various cultural backgrounds are unable to attain their highest

level of health for several reasons, including the social determinants of health, or those conditions in

which individuals are born, grow, live, work, and age (WHO, 2012), such as socioeconomic status,

education level, and the availability of health services (HHS ODPHP, 2010a). Though health inequities are

directly related to the existence of historical and current discrimination and social injustice, one of the

most changeable factors is the lack of culturally and linguistically appropriate services.

Health inequities result in disparities that directly affect the quality of life for all individuals. Health

disparities adversely affect neighborhoods, communities, and the broader society, thus making the issue

not only an individual concern but also a public health concern. In the United States, it has been

estimated that the combined cost of health disparities and subsequent deaths due to inadequate and/or

inequitable care is $1.24 trillion (LaVeist et al., 2009). Culturally and linguistically appropriate services are

increasingly recognized as effective in improving the quality of care and services (Beach et al., 2004;

Goode et al., 2006). By providing a structure to implement culturally and linguistically appropriate

services, the enhanced National CLAS Standards will improve an organization’s ability to address health

care disparities.

There are numerous ethical and practical reasons why providing culturally and linguistically appropriate

services in health and health care is necessary. The following reasons have been identified by the

National Center for Cultural Competence (Cohen & Goode, 1999, revised by Goode & Dunne, 2003):

1. To respond to current and projected demographic changes in the United States.

2. To eliminate long-standing disparities in the health status of people of diverse racial, ethnic

and cultural backgrounds.

3. To improve the quality of services and primary care outcomes.

4. To meet legislative, regulatory and accreditation mandates.

5. To gain a competitive edge in the market place.

6. To decrease the likelihood of liability/malpractice claims.

National Standards for CLAS in Health and Health Care:

A Blueprint for Advancing and Sustaining CLAS Policy and Practice

The Case for the Enhanced National CLAS Standards 15

The motivations for implementing CLAS are as varied as the approaches different stakeholders are taking

toward implementation, and depend upon the stakeholder’s mission, goals, and sphere of influence

(Betancourt, Green, Carrillo, & Park, 2005). The six reasons for the implementation of cultural

competency as described by the National Center for Cultural Competence fall into two frequently cited

overarching philosophies: one that pertains to social justice (e.g., Kumagai & Lypson, 2009; Sue, 2001)

and the other that pertains to standards of business (Brach & Fraser, 2002). Specifically, reasons number

one and number two are consistent with the social justice philosophy, which emphasizes diversity and the

improvement of services to underserved populations. The remaining reasons are consistent with the

standards of business philosophy, which focuses on strengthening business practices and business

development.

The enhanced National CLAS Standards align with the HHS Action Plan to Reduce Racial and Ethnic

Health Disparities (HHS, 2011) and the National Stakeholder Strategy for Achieving Health Equity

(National Partnership for Action to End Health Disparities, 2011a), which aim to promote health equity

through providing clear plans and strategies to guide collaborative efforts that address racial and ethnic

health disparities across the country. Similar to these initiatives, the enhanced National CLAS Standards

are intended to advance health equity, improve quality, and help eliminate health care disparities by

providing a blueprint for individuals and health and health care organizations to implement culturally and

linguistically appropriate services. Adoption of these Standards will help advance better health and health

care in the United States.

The following sections expound upon the reasons why culturally and linguistically appropriate services in

health and health care are necessary, as listed by the National Center for Cultural Competence.

Respond to Demographic Changes

It is projected that by 2050 the U.S. demographic makeup will be 47% non-Hispanic White, 29%

Hispanic, 13% Black and 9% Asian (Passel & Cohn, 2008). According to the most recent data,

approximately 20% of the U.S. population, or a little over 58 million people, speak a language other than

English at home, and of that 20%, almost 9% (over 24 million people) have limited proficiency in English

(Au, Taylor, & Gold, 2009; U.S. Census Bureau, 2010), which has implications for their proficiency in

health and health care (The Joint Commission, 2010). Given the increasing cultural diversity over the last

several decades (e.g., Genao, Bussey-Jones, Brady, Branch, & Corbie-Smith, 2003; Goode et al., 2006)

and the rapidly changing landscape of health and health care in the United States (Chin, 2000), there is

an increased need for health and health care professionals and organizations to provide effective, high-

quality care that is responsive to the diverse cultural and linguistic needs of individuals served.

The need for culturally and linguistically appropriate care is particularly great since similar demographic

changes have not occurred in the health and health care workforce (e.g., Genao et al., 2003; Institute of

National Standards for CLAS in Health and Health Care:

A Blueprint for Advancing and Sustaining CLAS Policy and Practice

The Case for the Enhanced National CLAS Standards 16

Medicine [IOM], 2004; Sullivan & Mittman, 2010). Given the important role that culture plays in health

and health behaviors (Kleinman, Eisenberg, & Good, 1978; Tseng & Streltzer, 2008), the lack of

workforce diversity is significant since it widens the cultural gap that already exists between health and

health care professionals and consumers, which subsequently contributes to the persistence of health

disparities (Brach & Fraser, 2000; Genao et al., 2003). The provision of culturally and linguistically

appropriate services can help to bridge this gap.

Eliminate Health Disparities

The prevalence of health disparities has been well-documented. For example, racial and ethnic minorities

have disproportionately higher rates of chronic disease and disability, higher mortality rates, and lower

quality of care, compared to non-Hispanic whites (e.g., Health Research & Educational Trust [HRET],

2011; IOM, 2003). In addition, even with expanded insurance coverage, racial minorities are less likely to

receive needed behavioral health services comparable to non-Latino Whites (Alegria, Lin, Chen, Duan,

Cook, & Meng, 2012). Health disparities exist beyond racial and ethnic groups; for example, individuals

with lower incomes are more likely to experience preventable hospitalizations compared to individuals

with higher incomes (HHS Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2011). In addition, lesbian

women are less likely to receive preventative cancer screenings than their heterosexual counterparts

(Buchmueller & Carpenter, 2010), and men who have sex with men are less likely to have access to

health and behavioral health care than the general population of men (e.g., Alvy, McKirnan, DuBois,

Ritchie, Fingerhut, & Jones, 2011; Buchmueller & Carpenter, 2010; McKirnan, DuBois, Alvy, & Jones,

2012).

The provision of culturally and linguistically appropriate services is increasingly recognized as a key

strategy to eliminating disparities in health and health care (e.g., Betancourt, 2004; 2006; Brach &

Fraser, 2000; HRET, 2011). Among several other factors, lack of cultural competence and sensitivity

among health and health care professionals has been associated with the perpetuation of health

disparities (e.g., Geiger, 2001; Johnson, Saha, Arbelaez, Beach, & Cooper, 2004). This is often the result

of miscommunication and incongruence between the patient or consumer’s cultural and linguistic needs

and the services the health or health care professional is providing (Zambrana, Molnar, Munoz, & Lopez,

2004). The provision of culturally and linguistically appropriate services can help address these issues by

providing health and health care professionals with the knowledge and skills to manage the provider-

level, individual-level, and system-level factors referenced in the Institute of Medicine’s seminal report

Unequal Treatment

that intersect to perpetuate health disparities (IOM, 2003).

National Standards for CLAS in Health and Health Care:

A Blueprint for Advancing and Sustaining CLAS Policy and Practice

The Case for the Enhanced National CLAS Standards 17

Improve Quality of Services and Care

Health and health care professionals and organizations strive to provide high quality services that meet

the needs of all the individuals they serve. High quality care and services are those provided respectfully

and equitably to all populations served (American Medical Association [AMA], 2006; IOM, 2001). A

commitment to high quality services and care is often reflected in organizations’ mission statements or

core values.

Culture influences health beliefs and practices, as well as health seeking behavior and attitudes (IOM,

2003). When health and health care professionals are aware of culture’s influence on health beliefs and

practices, they can use this awareness to consider and address issues such as access to care. This is just

one example of how culturally and linguistically appropriate services can help improve health and health

care quality (Betancourt, 2006). Culturally and linguistically appropriate services are increasingly

recognized as effective in improving the quality of services (Beach et al., 2004; Goode et al., 2006),

increasing patient safety (e.g., through preventing miscommunication, facilitating accurate assessment

and diagnosis), enhancing effectiveness, and underscoring patient-centeredness (e.g., Betancourt, 2006;

Brach & Fraser, 2000; Thom, Hall, & Pawlson, 2004).

Meet Legislative, Regulatory, and Accreditation Mandates

Culturally and linguistically appropriate services are increasingly included in or referenced by local and

national legislative, regulatory, and accreditation mandates. For example, the Patient Protection and

Affordable Care Act (the Affordable Care Act), Pub. L. No. 111-148 (2010), as amended by the Health

Care and Education Reconciliation Act of 2012, Pub. L. No. 111-152 (2012), referred to collectively as the

Affordable Care Act, contains several provisions related to culturally and linguistically appropriate

services. Section 1311(i)(3)(E) of the Affordable Care Act requires that outreach and education efforts by

Navigators – entities that receive grants from health insurance exchanges created under the Affordable

Care Act to assist individuals in accessing and taking advantage of the exchanges – be culturally and

linguistically appropriate. Furthermore, under sections 2715 and 2719 of the Public Health Service Act as

amended by the Affordable Care Act, insurance companies are required to provide certain disclosures and

notices in a culturally and linguistically appropriate manner.

National Standards for CLAS in Health and Health Care:

A Blueprint for Advancing and Sustaining CLAS Policy and Practice

The Case for the Enhanced National CLAS Standards 18

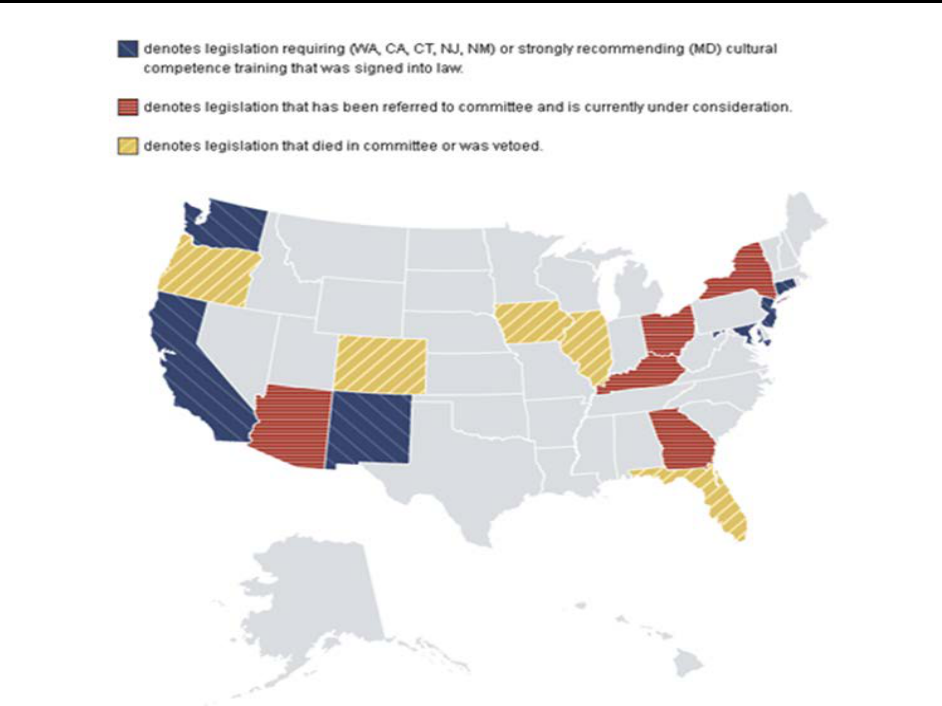

Figure 1: State Legislation

In addition, under Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, as implemented by Executive Order 13166,

organizations receiving federal funds must take reasonable steps to provide meaningful access to their

programs for individuals with limited English proficiency (Executive Order no. 13,166, 2000).

Furthermore, several states have recognized the importance of cultural and linguistic competency by

legislating cultural and linguistic competency training in health care. These mandates help state health

agencies incorporate cultural and linguistic competency into the health services they provide. As of 2012,

six states have moved to mandate some form of cultural and linguistic competency for either all or a

component of its health care workforce (see Figure 1) (HHS OMH Think Cultural Health, 2012).

Accrediting bodies such as The Joint Commission and the National Committee for Quality Assurance have

established accreditation standards that target the improvement of communication, cultural competency,

patient-centered care, and the provision of language assistance services (Briefer French, Schiff, Han, &

Weinick, 2008; Wilson-Stronks & Galvez, 2007).

National Standards for CLAS in Health and Health Care:

A Blueprint for Advancing and Sustaining CLAS Policy and Practice

The Case for the Enhanced National CLAS Standards 19

Gain a Competitive Edge in the Market Place

Culturally and linguistically appropriate services can also help health and health care professionals and

organizations gain a competitive edge in the market place. Although the implementation of culturally and

linguistically appropriate services certainly requires resources, there are numerous business-related

advantages to investing these resources. By implementing culturally and linguistically appropriate services

– including the provision of communication and language assistance, as well as partnerships with the

community – an organization can develop a positive reputation in the service area and therefore expand

its market share. The provision of effective, equitable, understandable, and respectful quality care and

services helps cultivate a loyal consumer base, which then solidifies this market share (AMA, 2006).

As the American Medical Association notes, “a loyal consumer base helps organizations avoid costly

problems, such as high turnover, low utilization rates, and unused capacity” (AMA, 2006, p. 112). In

addition, culturally and linguistically appropriate services, such as assessments of community health

assets and needs, help organizations tailor their services, making the services more cost-effective (e.g.,

Hornberger, Itakura, & Wilson, 1997).

Overall, culturally and linguistically competent practices can help organizations gain a competitive edge in

the market place, as illustrated in the following examples (Alliance of Community Health Plans

Foundation, 2007):

o Holy Cross Hospital in Maryland increased its market share among individuals with limited

English proficiency by creating 68 individual maternity suites with a substantial cultural

competency component in their design. Deliveries at the maternity suites increased from

7,300 to 9,300 annually.

o Contra Costa Health Services in California implemented a Remote Video/Voice Medical

Interpretation Project, which increased the overall effectiveness of interpretation services.

With the addition of this service, the hospital serves twice the number of patients it did

before the service was available, and for significantly lower costs.

Decrease the Risk of Liability

The literature illustrates the vital role communication plays in avoiding cases of malpractice due to

diagnostic and treatment errors (Goode et al., 2006). When communicating with culturally and

linguistically diverse populations, the opportunity for miscommunication and misunderstanding increases,

which subsequently increases the likelihood of errors (Youdelman & Perkins, 2005). These errors, in turn,

can cost millions of dollars in liability or malpractice claims. Culturally and linguistically appropriate

services can reduce the possibility of such errors. For example, a first responder in Florida misinterpreted

National Standards for CLAS in Health and Health Care:

A Blueprint for Advancing and Sustaining CLAS Policy and Practice

The Case for the Enhanced National CLAS Standards 20

a single Spanish word, “intoxicado,” to mean "intoxicated" rather than its intended meaning of "feeling

sick to the stomach." This led to a delay in diagnosis, which resulted in a potentially preventable case of

quadriplegia, and ultimately, a $71 million malpractice settlement (Flores, 2006).

The HHS Health Resources and Services Administration [HRSA] found that health professionals who lack

cultural and linguistic competency can be found liable under tort principles in several areas (2005). For

instance, providers may be presumed negligent if an individual is unable to follow guidelines because

they conflict with his/her beliefs and the provider neglected to identify and try to accommodate the

beliefs (HRSA, 2005). Additionally, if a provider proceeds with treatment or an intervention based on

miscommunication due to poor quality language assistance, he/she and his/her organization may face

increased civil liability exposure (DeCola, 2010). Thus, culturally and linguistically appropriate

communication is essential to minimize the likelihood of liability and malpractice claims.

National Standards for CLAS in Health and Health Care:

A Blueprint for Advancing and Sustaining CLAS Policy and Practice

The Enhanced National CLAS Standards 21

The Enhanced National CLAS Standards

The Standards

The enhanced National Standards for Culturally and Linguistically Appropriate Services in Health and

Health Care from the Office of Minority Health at the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services are

composed of 15 Standards that provide individuals and organizations with a blueprint for successfully

implementing and maintaining culturally and linguistically appropriate services. Culturally and linguistically

appropriate health care and services, broadly defined as care and services that are respectful of and

responsive to the cultural and linguistic needs of all individuals, are increasingly seen as essential to

reducing disparities and improving health care quality.

All 15 Standards are necessary to advance health equity, improve quality, and help eliminate health care

disparities. As important as each individual Standard is, the exclusion of any Standard diminishes health

professionals’ and organizations’ ability to meet an individual’s health and health care needs in a culturally

and linguistically appropriate manner. Thus, it is strongly recommended that each of the 15 Standards be

implemented by health and health care organizations.

Purpose

The purpose of the enhanced National CLAS Standards is to provide a blueprint for health and health care

organizations to implement culturally and linguistically appropriate services that will advance health

equity, improve quality, and help eliminate health care disparities.

Audience

All members of the health and health care community can benefit from the framework offered by the

enhanced National CLAS Standards. The enhanced National CLAS Standards are directed toward a

broader audience than the original Standards in order to address more fully every point of contact

throughout the health care and health services continuum. A wide spectrum of professionals and

organizations influence health and health care every day. The following is a partial list of audiences of the

enhanced National CLAS Standards and how each type of audience might utilize them:

o

Accreditation and Credentialing Agencies:

to assess and compare health care facilities,

health and human service organizations, and providers who offer culturally and linguistically

appropriate services and ensure quality for diverse populations. Institutions such as The Joint

Commission and the National Committee for Quality Assurance have made great strides in

implementing policies and standards to help ensure these quality services.

National Standards for CLAS in Health and Health Care:

A Blueprint for Advancing and Sustaining CLAS Policy and Practice

The Enhanced National CLAS Standards 22

o

Community-Based Organizations:

to promote quality health care for diverse populations and

to assess and monitor care and services being delivered. The potential advocate audience is

broad and includes: legal services, consumer education agencies, faith-based organizations, and

other local, regional, or national nonprofit organizations that address health and health care

issues.

o

Educators:

to incorporate cultural and linguistic competency into their curricula and to raise

awareness about the impact of culture and language on health and health care services. This

audience would include educators from academic institutions, state health professional licensing

agencies, and educators from legal and social service professions.

o

Governance and Leadership:

to draft consistent and comprehensive laws, regulations, and

contract language. This audience would include federal, state, tribal, and local governments. The

audience would also include the individuals within organizations who are responsible for

developing regulations and contracts, as well as the leadership responsible for decision making

regarding regulations and contracts.

o

Health Care and Service Providers:

to incorporate cultural and linguistic competency into the

delivery of quality health care and services. This audience would include clinicians, practitioners,

and service delivery organizations across health and allied health disciplines, including behavioral

health.

o

Health and Health Care Staff and Administrators:

to implement culturally and linguistically

appropriate services throughout an organization, at every point of contact. This audience would

include employees, contractors, and volunteers serving throughout the organization.

o

Patients/Consumers:

to understand their right to receive accessible and appropriate health

and health care services and to evaluate whether providers can offer them.

o

Public Health Workforce:

to implement cultural and linguistic competency into the provision of

public health services. This audience would include those involved in the behavioral health,

emergency medical services, environmental health, epidemiology, and global health.

o

Purchasers:

to promote the needs of diverse consumers of health benefits, and leverage

responses from insurers and health plans. This audience would include government and employer

purchasers of health benefits.

National Standards for CLAS in Health and Health Care:

A Blueprint for Advancing and Sustaining CLAS Policy and Practice

The Enhanced National CLAS Standards 23

Components of the Standards

The enhanced National CLAS Standards are built upon the groundwork laid by the original Standards

developed in 2000. The enhanced Standards incorporate broader definitions of culture and health and

aim to reach a broader audience, in an effort to ensure that every individual has the opportunity to

receive culturally and linguistically appropriate health care and services.

The enhanced National CLAS Standards are organized into one Principal Standard and three themes: (1)

Governance, Leadership, and Workforce; (2) Communication and Language Assistance; and (3)

Engagement, Continuous Quality Improvement, and Accountability. Individuals and organizations may

identify or utilize additional standards that are relevant to their mission and services and are encouraged

to add to the National CLAS Standards.

Strategies for Implementation

Implementation of the National CLAS Standards will vary from organization to organization. Therefore,

organizations should identify the best implementation methods appropriate to their size, mission, scope,

and type of services offered. It is also important to develop measures to examine the effectiveness of the

programs being implemented, identify areas for improvement, and identify next steps. Many of these

measures and evaluation strategies may already be in place throughout an organization for the purposes

of accreditation and grant management. Health and human service providers, emergency responders,

community-based organizations, and health care delivery sites (e.g., hospitals, clinics, and community

health centers) will have different goals and expectations for the National CLAS Standards. Therefore,

their strategies for implementation may differ widely.

The enhanced National CLAS Standards and

The Blueprint

include specific implementation strategies to

further the establishment or expansion of culturally and linguistically appropriate services. Prior to

implementation, it is important to have a vision of what culturally and linguistically appropriate services

would look like within the organization and to identify available and required resources (e.g., structure,

funding, and personnel) to ensure success.

Responsibilities associated with implementing the enhanced National CLAS Standards should be

distributed throughout the organization to ensure comprehensive engagement and effectiveness so that

no single individual or department bears the responsibility for the entire organization. For example, some

organizations find it helpful to establish an interdisciplinary or cross-departmental committee that will

help identify, implement, and sustain the elements of a well-developed CLAS plan.

National Standards for CLAS in Health and Health Care:

A Blueprint for Advancing and Sustaining CLAS Policy and Practice

Enhancements to the National CLAS Standards 24

Enhancements to the National CLAS Standards

Data collected during the HHS Office of Minority Health’s National Standards for Culturally and

Linguistically Appropriate Services in Health and Health Care Enhancement Initiative supported the notion

that it was time for an enhancement of the original National CLAS Standards. In the beginning stages of

the Enhancement Initiative, a majority of individuals who provided public comment on the original

National CLAS Standards indicated that though the Standards met their needs as a whole, additional

guidance or direction was needed.

More specifically, individuals and organizations who provided public comment sought clarification on the

Standards’ intention, terminology, and implementation strategies. There was also strong support, from

public comment, the Advisory Committee, and a literature review, for expanding the concepts of health

and culture. The enhanced National CLAS Standards and

The Blueprint

aim to address these issues. The

format of

The Blueprint

reflects the suggestions provided during the public comment period.

The past decade has shown that the National CLAS Standards are dynamic in nature. Therefore, as best

and promising practices develop in the field of cultural and linguistic competency, there will be future

enhancements of the National CLAS Standards. In addition, the Web version of

The Blueprint

will be

updated periodically with additional information and resources as the Standards are disseminated in the

field and as new information is gathered regarding promising implementation and management

strategies.

The following sections discuss the enhancements made to the National CLAS Standards.

Culture

The enhanced National CLAS Standards have adopted an expanded, broader definition of culture.

Specifically, in the enhanced National CLAS Standards, culture refers to “the integrated pattern of

thoughts, communications, actions, customs, beliefs, values, and institutions associated, wholly or

partially, with racial, ethnic, or linguistic groups, as well as with religious, spiritual, biological,

geographical, or sociological characteristics.” This definition is adapted from other widely accepted

definitions of culture (e.g., Gilbert et al., 2007; HHS OMH, 2005) and attempts to reflect the complex and

dynamic nature of culture, as well as the numerous ways in which culture has been defined and studied

across multiple disciplines. Refer to the table below for additional discussion of aspects of culture.

There is considerable recognition that every patient-provider interaction is a cross-cultural interaction and

that the scope of cultural competency in health care should expand to address multiple markers of

difference (Khanna, Cheyney, & Engle, 2009; IOM, 2003). The broader definition of culture adopted in

the enhanced National CLAS Standards mirrors other leading initiatives in the field in terms of scope,

National Standards for CLAS in Health and Health Care:

A Blueprint for Advancing and Sustaining CLAS Policy and Practice

Enhancements to the National CLAS Standards 25

including Healthy People 2020 from the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS ODPHP, 2010a)

and The Joint Commission (

Advancing Effective Communication, Cultural Competence, and Patient- and

Family-Centered Care: A Roadmap for Hospitals

, 2010). In addition, with the recognition that culture

includes multiple facets and markers of difference, there is an increased opportunity for health

professionals to identify and use similarities to improve health and health care interactions.

National Standards for CLAS in Health and Health Care:

A Blueprint for Advancing and Sustaining CLAS Policy and Practice

Enhancements to the National CLAS Standards 26

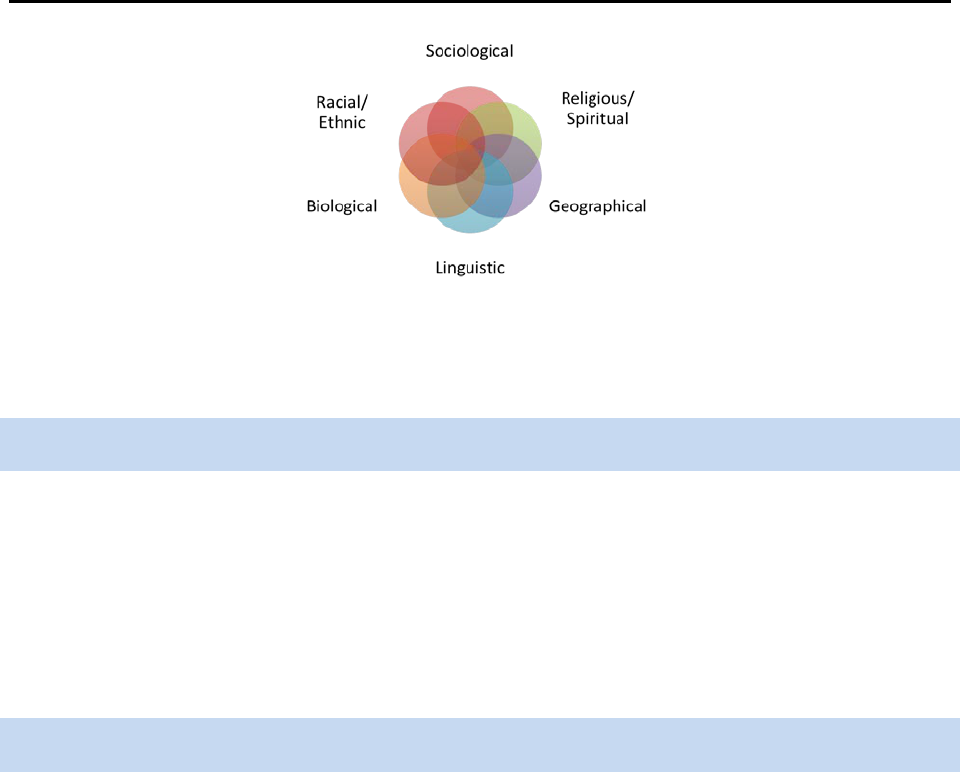

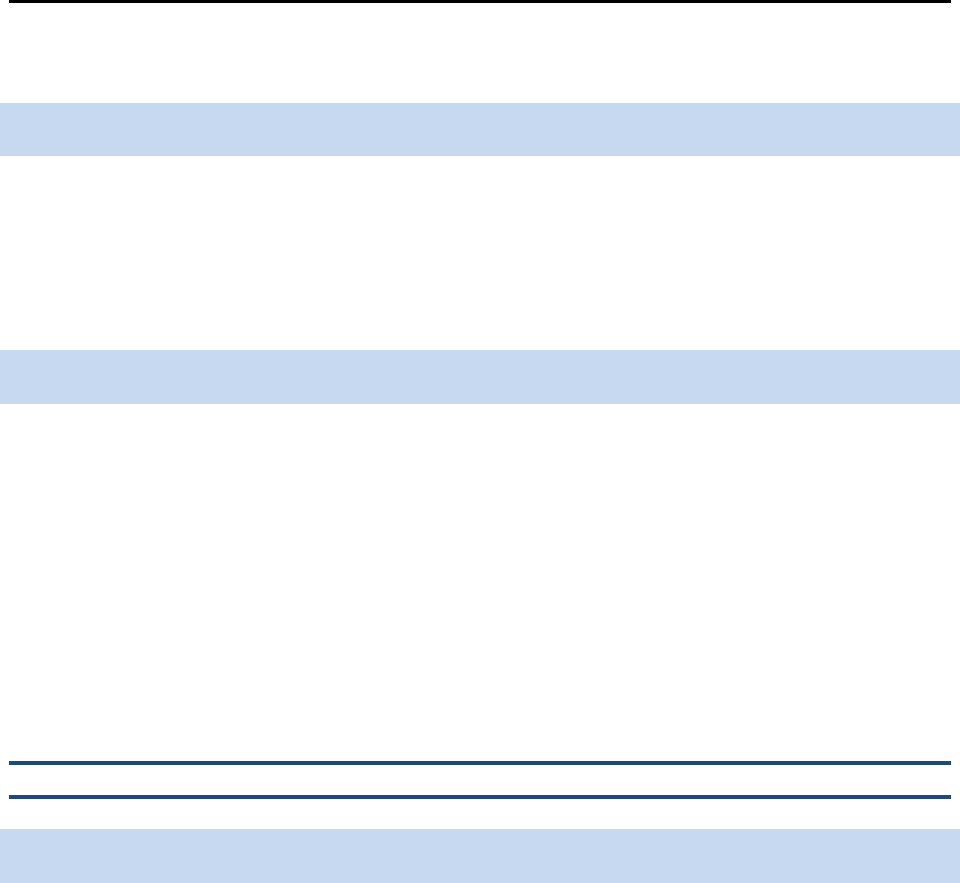

I

ndividuals do not experience their lives or their health through a single lens of identity (e.g., solely race,

gender, or religious); rather, many elements inform their perceptions, beliefs, customs, and reactions

(e.g., Frable, 1997). Figure 2 depicts various aspects of culture through which an individual may

frequently experience his/her cultural identity. For example, an individual’s religious/spiritual

characteristics often overlap with and are informed by the sociological and racial/ethnic groups with

which he/she identifies (e.g., an African American Christian male may experience the world

simultaneously by his race, sex, and religious beliefs). Each of the circles within Figure 2 represents a

very broad area of culture, as described within the definition. These areas are by no means exhaustive,

as there are many other aspects of cultural identity.

National Standards for CLAS in Health and Health Care:

A Blueprint for Advancing and Sustaining CLAS Policy and Practice

Enhancements to the National CLAS Standards 27

(Graves, 2001, revised 2011)

Figure 2: Interrelationship of Aspects of Culture

Health

Health encompasses many aspects, including physical, mental, social, and spiritual well-being (HHS IHS,

n.d.; HHS OSG et al., 2012; WHO, 1946). The World Health Organization also notes that health is “not

merely the absence of disease or infirmity” (WHO, 1946). From this perspective, health status falls along

a continuum and therefore can range from poor to excellent. In addition, how individuals experience

health and define their well-being is greatly informed by their cultural identity. The advancement of

health equity allows the attainment of the highest level of health for all people.

Health and Health Care Organizations

Adopting a more comprehensive conceptualization of health requires, by extension, a more inclusive

recognition of the variety of professionals and organizations providing the related care and services. The

enhanced National CLAS Standards reference both health

and

health care organizations and professionals

to acknowledge those working not only in health care delivery facilities (e.g., hospitals, clinics, community