1

Airmail: A Brief History

The air mail route is the first step toward the universal commercial use of the

aeroplane.

—Benjamin B. Lipsner, Superintendent of Aerial Mail Service, 1918

1

When airmail began in 1918, airplanes were still a fairly new invention. Pilots

flew in open cockpits in all kinds of weather, in planes later described as “a

nervous collection of whistling wires, of linen stretched over wooden ribs, all

attached to a wheezy, water-cooled engine.”

2

A 1918 article titled “Practical

Hints on Flying” advised pilots “never forget that the engine may stop, and at

all times keep this in mind.”

3

Pilots followed landmarks on the ground; in fog

they flew blind. Unpredictable weather, unreliable equipment, and

inexperience led to frequent crashes; 34 airmail pilots died from 1918 through

1927. Gradually, through trial and error and personal sacrifice, U.S. Air Mail

Service employees developed reliable navigation aids and safety features for

planes and pilots. They demonstrated that flight schedules could be safely

maintained in all kinds of weather. Then they created lighted airways and

proved that night flying was possible. Once the Post Office Department had

proven the viability of commercial flight, airmail service was turned over to

private carriers, flying under contract with the Department. In the days before

passenger service, revenue from airmail contracts sustained commercial

airlines.

First U.S. Mail Flights, 1911

On June 14, 1910, Representative Morris Sheppard of Texas introduced a

bill to authorize the Postmaster General to investigate the feasibility of “an

aeroplane or airship mail route.”

4

The bill died in committee. The New York

Telegraph deemed airmail service a fanciful dream, predicting that, when it

was offered:

Love letters will be carried in a rose-pink aeroplane, steered by Cupid’s

wings and operated by perfumed gasoline. … [and] postmen will wear

wired coat tails and on their feet will be wings.

5

Frank Hitchcock, Postmaster General from 1909 to 1913, was keenly

interested in the development of airplanes. He was convinced they could be

used for mail transportation. In November 1910, at an aviation meet in

Baltimore attended by top government officials, thousands of spectators

cheered when Hitchcock agreed to fly as a passenger in a Bleriot

monoplane. In an article subtitled “Postmaster General Brave,” The Baltimore

Sun reported:

Mr. Hitchcock liked it. … The wind grasped the machine … and shook it,

but Mr. Hitchcock sat tight. Three minutes after he started he had landed

on the earth once more. ‘It will not be long before we are carrying the

mails this way, that is certain,’ he said as he climbed out.

6

In September 1911, Hitchcock authorized mail flights at an aviation meet on

Long Island, New York — the first authorized U.S. mail flights.

7

Eight pilots

were sworn in as “aeroplane mail carriers” for the event, which ran from

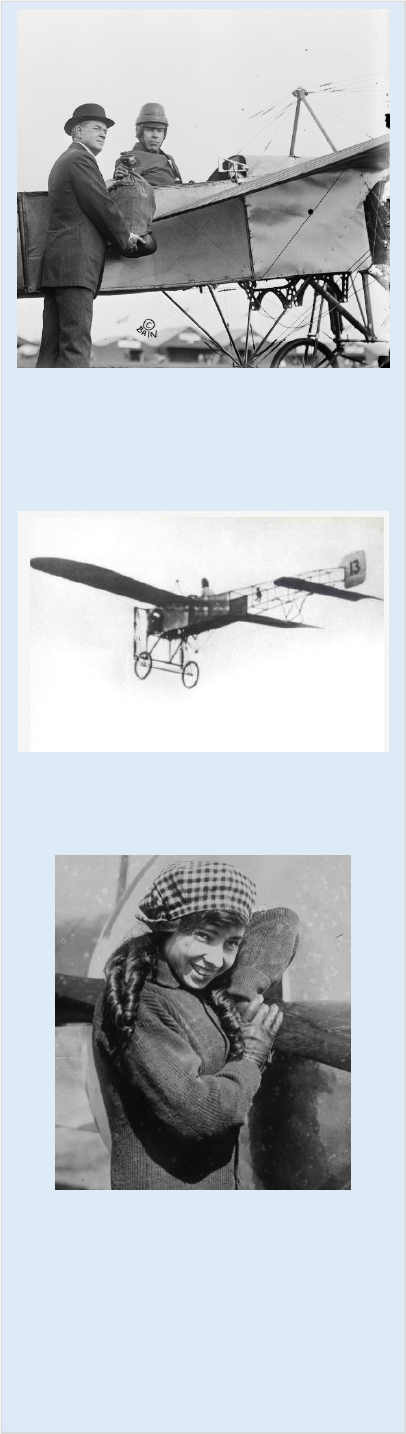

First authorized U.S. Mail flights, 1911

Courtesy Library of Congress

Postmaster General Frank Hitchcock hands

pilot Earle Ovington a mailbag at an aviation

meet in Mineola, NY, on September 25, 1911,

two days after Ovington’s historic first flight.

Earle Ovington, 1911

On September 23, 1911, Earle Ovington

piloted the first authorized U.S. Mail flight in

his Bleriot monoplane.

Katherine Stinson, the “Flying Schoolgirl”

Courtesy Library of Congress

In 1913, 22-year-old Katherine Stinson

became the first woman to fly the U.S. Mail

when she dropped mailbags from her plane at

the Montana State Fair. Stinson captivated

audiences worldwide with her fearless feats of

aerial derring-do. In 1918, she became the first

woman to fly both an experimental mail route

from Chicago to New York and the regular

route from New York to Washington, D.C.

2

September 23 to October 1, 1911. Aviator Earle Ovington had the

distinction of piloting the first history-making flight, on September

23. The pilots made daily flights from Garden City Estates to

Mineola, New York, dropping mailbags from the plane to the

ground where they were picked up by Mineola’s Postmaster,

William McCarthy.

In the next few years the Department authorized dozens more

experimental flights at fairs, carnivals, and air meets in more than

20 states. These flights convinced Department officials that

airplanes could carry mail. Beginning in 1912, postal officials urged

Congress to appropriate money to launch airmail service.

8

In 1916,

Congress finally authorized the use of $50,000 from steamboat and

powerboat service appropriations for airmail experiments. The

Department advertised for bids for contract service in

Massachusetts and Alaska, but received no acceptable responses.

In 1917, Congress appropriated $100,000 to establish experimental

airmail service the next fiscal year.

9

The Post Office Department

advertised for bids for airplanes in February 1918, but cancelled the

solicitation just weeks later after conferring with the Army Signal

Corps. The Army wanted to operate the airmail service, to give its

pilots more cross-country flying experience. The Postmaster

General and the Secretary of War reached an agreement: the Army

Signal Corps would lend its planes and pilots to the Department to

start an airmail service.

Start of Scheduled Airmail Service, 1918

The Post Office Department began scheduled airmail service

between New York and Washington, D.C., on May 15, 1918 — an

important date in commercial aviation. Simultaneous takeoffs were

made from Washington’s Polo Grounds and from Belmont Park,

Long Island — both trips by way of Philadelphia.

During the first three months of operation, the Post Office

Department used Army pilots and six Army Curtiss JN-4H “Jenny”

training planes. On August 12, 1918, the Department took over all

phases of airmail service, using newly hired civilian pilots and

mechanics, and six specially built mail planes from the Standard

Aircraft Corporation.

These early mail planes had no reliable instruments, radios, or

other navigational aids. Pilots navigated using landmarks and dead

reckoning. Forced landings occurred frequently due to bad

weather, but fatalities in the early months were rare, largely

because of the planes’ small size, maneuverability, and slow

landing speed.

Congress authorized airmail postage of 24 cents per ounce,

including special delivery. The rate was lowered to 16 cents on

July 15, 1918, and to 6 cents on December 15 (without special

delivery).

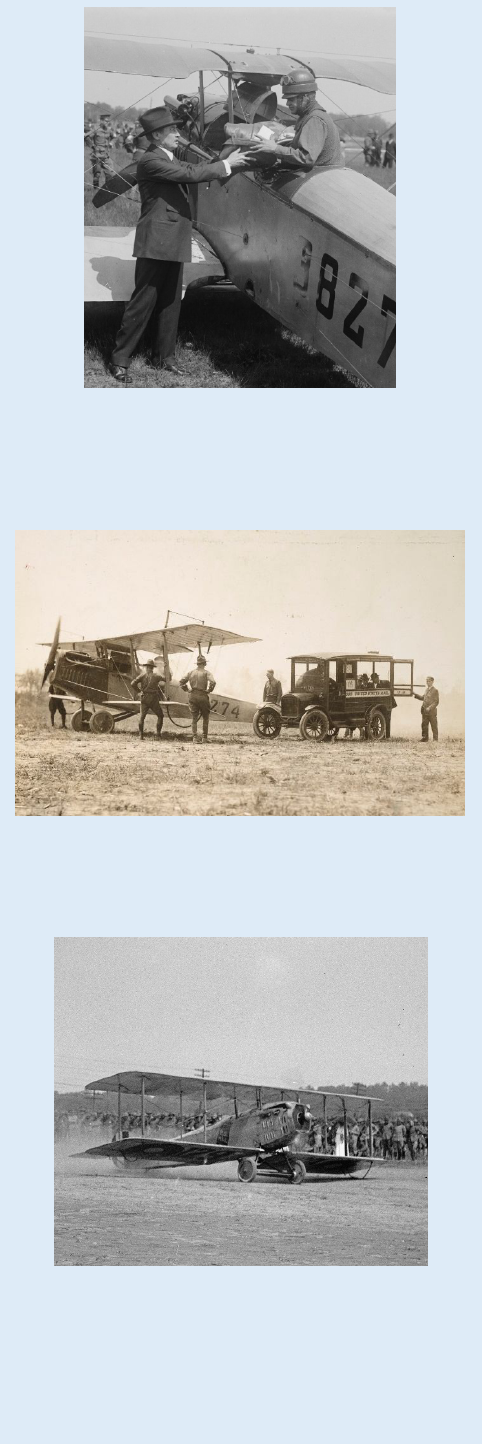

First day of scheduled airmail service, Belmont

Park, New York, 1918

Courtesy Library of Congress

Postmaster Thomas Patten of New York hands mail to

Army Lieutenant Torrey Webb in his Curtiss JN-4H

"Jenny" airplane on May 15, 1918.

First day of scheduled airmail service, Bustleton

Field, Pennsylvania, 1918

Courtesy National Archives

Mail from Philadelphia is loaded onto a Curtiss JN-4H

bound for New York on May 15, 1918.

First civilian airmail flight, August 1918

Courtesy Library of Congress

On August 12, 1918, Max Miller, one of the first civilian

airmail pilots, took off for Philadelphia from the College

Park, Maryland, airfield, which replaced Washington’s

tree-ringed Polo Grounds as the city’s airfield. Miller flew

one of the new Standard JR-1B mail planes purchased

by the Department.

3

Still, the public was reluctant to use this more expensive service,

which was just a few hours quicker than regular service by train.

During the first year, airmail bags often contained as much regular

mail as airmail.

Transcontinental Route, 1920

To better its delivery time on long hauls and entice the public to

use airmail, the Department’s long-range plans called for a

transcontinental air route from New York to San Francisco. The

first legs of this transcontinental route — from New York to

Cleveland with a stop at Bellefonte, Pennsylvania, then from

Cleveland to Chicago, with a stop at Bryan, Ohio — opened in

1919. A third leg opened in 1920 from Chicago to Omaha, via Iowa

City, and feeder lines were established from St. Louis and

Minneapolis to Chicago. The last transcontinental segment — from

Omaha to San Francisco, via North Platte, Nebraska; Cheyenne,

Rawlins, and Rock Springs in Wyoming; Salt Lake City, Utah; and

Elko and Reno in Nevada — opened on September 8, 1920.

Initially, mail was carried on trains at night and flown by day. Still,

the service was 22 hours faster than the cross-country all-rail time.

In August 1920, the Department began installing radio stations at

each airfield to provide pilots with current weather information. By

November, ten stations were operating, including two Navy

stations. When airmail traffic permitted, other government

departments used the radios for special messages, and the

Department of Agriculture used the radios to transmit weather

forecasts and stock market reports.

Regular Night Flying, 1924

Before the air mail service can offer … its full measure of value it

will be necessary to operate the planes at night as well as in the

daytime.

—Postmaster General Harry S. New, 1923

10

To demonstrate the possible speed of airmail, the Department

staged a through-flight from San Francisco to New York on

February 22, 1921 — the first time mail was flown both day and

night over the entire distance. Winter was not an ideal season for

test flights, but the Department was pressed — Congress was

deciding whether or not, and to what extent, to continue to fund

airmail service. Despite bad weather, the flight was a success,

largely through the heroic efforts of pilot Jack Knight (see at right).

Congress was impressed. Instead of ending the service, Congress

appropriated $1,250,000 for its expansion, and later increased the

amount.

To prepare for night flying, the Post Office Department equipped its

planes with luminescent instruments, navigational lights, and

parachute flares. In 1923, it began building a lighted airway along

the transcontinental route, to guide pilots at night. The first section

completed was Chicago to Cheyenne, 885 miles. Emergency

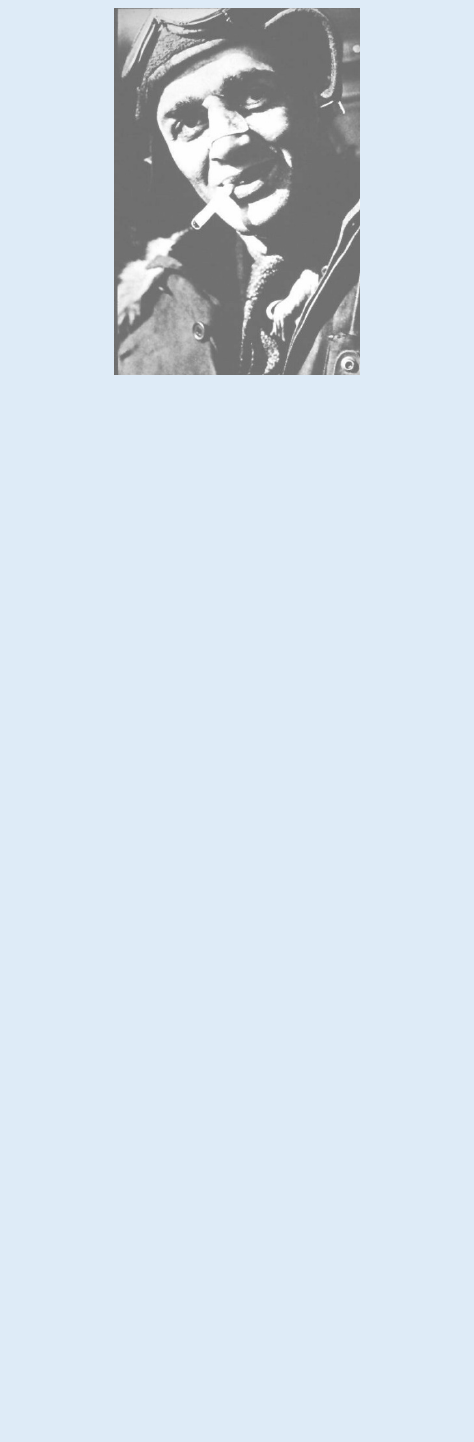

Jack Knight, “The Hero Who Saved Airmail,” 1921

Courtesy Smithsonian’s National Postal Museum

On February 22, 1921, the first daring, round-the-clock,

transcontinental airmail flight started out with four

planes. Two westbound planes left New York’s

Hazelhurst Field while two eastbound planes left San

Francisco. One of the westbound trips abruptly ended

when icing forced the pilot down in a Pennsylvania

field. The other was halted by a snowstorm in Chicago.

One of the eastbound pilots fared even worse —

William E. Lewis crashed and died near Elko, Nevada.

The mail was salvaged and loaded onto another

eastbound plane.

It was after dark when the airmail reached North Platte,

Nebraska, and pilot Jack Knight was ready to fly the

next leg of the relay, to Omaha. A former Army flight

instructor, Knight looked bad and felt worse, suffering a

broken nose and bruises from a crash landing the week

before in Wyoming. He had flown to Omaha many

times — but never at night.

Knight’s first taste of night-flying was nerve-wracking.

Residents of the towns below lit bonfires to help mark

the route. As the weather worsened, Knight set down in

Omaha, wind-chilled, famished and exhausted. Then

he got more bad news: the pilot scheduled to fly the

next leg, to Chicago, was a no-show. Though the route

was unfamiliar, Knight volunteered to fly the mail to

Chicago himself.

Between Omaha and Chicago lay a refueling stop in

Iowa City, which Knight had never seen in the daytime,

let alone at night in a snowstorm. There were no

bonfires or beacons marking the airfield — the ground

crew had gone home, assuming the flight had been

canceled — but by some miracle Knight found it. He

buzzed the field until the night watchman heard his

airplane and lit a flare. After landing and refuelling he

was back in the cockpit. He touched down at Maywood

Field, outside Chicago, at 8:40 a.m. The mailbags were

quickly loaded onto a plane bound for Cleveland and

then the final stretch to New York.

The mail from San Francisco reached New York in

record time — 33 hours and 20 minutes. Newspapers

hailed Knight as the “hero who saved the airmail.”

Congress, which had debated eliminating funding for

airmail, instead increased it.

4

landing fields were created every 25 miles, between the 5 regular

landing fields in that section. All the fields were marked by fifty-foot

towers with revolving beacon lights. At the regular fields, the

beacons were visible for up to 150 miles; beacons at the emergency

fields were visible for up to 80 miles. Small white lights outlined the

fields’ boundaries. Between landing fields, 289 flashing gas

beacons —visible for up to 9 miles — were installed every 3 miles

from Chicago to Cheyenne.

11

In 1922 and 1923, the Department was awarded the Collier Trophy

for important contributions to the development of aeronautics,

especially in safety and for demonstrating the feasibility of night

flights.

The Department extended the lighted airway eastward to Cleveland

and westward to Rock Springs, Wyoming, in 1924. In 1925, the

lighted airway stretched from New York to Salt Lake City.

Regular cross-country through service, with night flying, began on

July 1, 1924. In 1926, the trip from New York to San Francisco

included 15 stops for service and the exchange of mail. Pilots and

planes changed six times en route, at Cleveland, Chicago, Omaha,

Cheyenne, Salt Lake City, and Reno. The longest leg was between

Omaha and Cheyenne, 476 miles; the shortest, 184 miles, was

between Reno and San Francisco.

Charles I. Stanton, an early airmail pilot and airmail division

superintendent who later headed the Civil Aeronautics

Administration, said about the early days of scheduled airmail

service:

We planted four seeds. … They were airways, communications,

navigation aids, and multi-engined aircraft. Not all of these

came full blown into the transportation scene; in fact, the last

one withered and died, and had to be planted over again nearly

a decade later. But they are the cornerstones on which our

present world-wide transport structure is built, and they came,

one by one, out of our experience in daily, uninterrupted flying

of the mail.

12

Service Contracted Out, 1926

Our activities in the air have been directed toward the performance

of an important public service in a manner to demonstrate to men of

means that commercial aviation is a possibility.

—Postmaster General Harry S. New, 1925

13

On February 2, 1925, Congress authorized the Postmaster General

to contract for airmail service. The Post Office Department

immediately invited bids from commercial aviation companies. The

first commercial airmail flight in the United States occurred

February 15, 1926. By the end of 1926, 11 out of 12 contracted

airmail routes were operating.

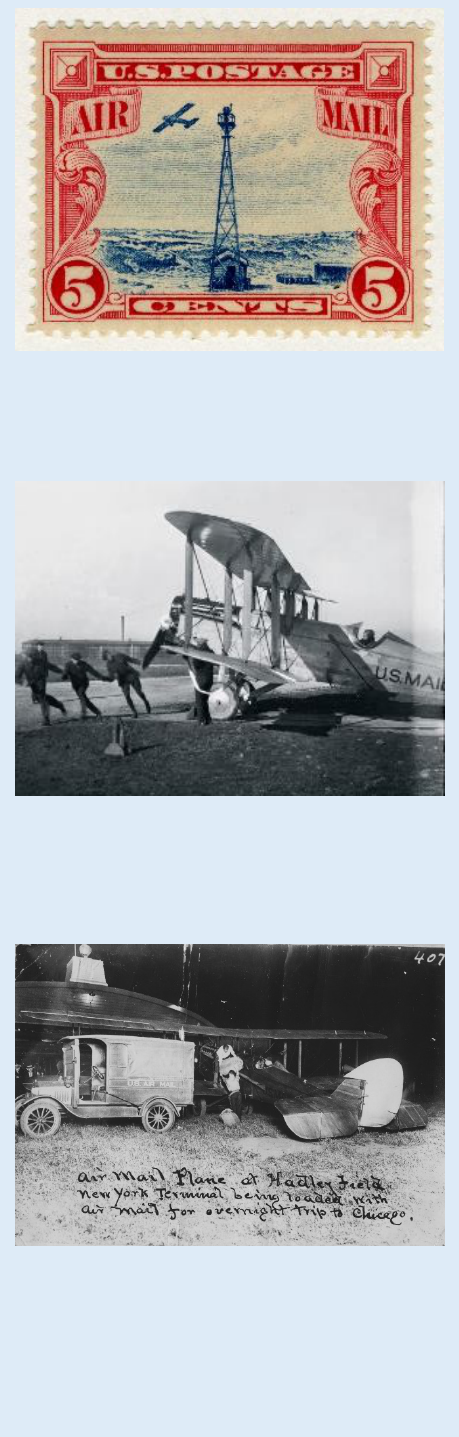

Beacon on Rocky Mountains stamp, 1928

Courtesy Smithsonian’s National Postal Museum

The 5-cent airmail stamp issued on July 25, 1928,

depicted the beacon light tower at the emergency

airmail landing field near Sherman, Wyoming.

Starting the engine, 1920s

In 1921 the Department adopted the DeHavilland DH-

4 as its standard mail plane. Some of its DH-4s were

surplus planes from World War I, modified to fly the

mail. It took three men to crank the DH-4's 400-

horsepower Liberty engine when it was cold.

Preparing for overnight flight, circa 1925

A DeHavilland DH-4 is loaded at Hadley Field, New

Jersey (the New York terminal), for an overnight trip

to Chicago. Overnight service between New York and

Chicago began on July 1, 1925. The westbound trip

took 9 hours and 15 minutes. Planes and pilots

changed at Cleveland.

5

As commercial airlines took over, the Department transferred its

lights, airways, and radio service to the Department of Commerce,

including 17 fully equipped stations, 89 emergency landing fields,

and 405 beacons. Terminal airports, except government properties

in Chicago, Omaha, and San Francisco, were transferred to the

municipalities in which they were located. Some planes were sold

to airmail contractors, while others were transferred to interested

government departments. By September 1, 1927, all airmail was

carried under contract.

Although the first airmail contracts yielded little or no profit to the

carriers, changes to federal law in 1928 granted carriers both

increased compensation and the potential for 10-year exclusive

rights to the routes they carried.

14

The Airmail Act of 1930 provided for compensation to carriers

based on carrying capacity, versus mail actually carried, and

continued the Postmaster General’s authority to grant 10-year

exclusive rights to successful performers.

15

The act also gave

Postmaster General Walter Brown (1929–1933) broad authority to

re-shape airmail contracts and routes — authority he was later

charged with exceeding.

Charges of fraud and collusion in the award and extension of

airmail contracts at the so-called “spoils conferences” of 1930

caused Brown’s successor, James Farley, to cancel all domestic

airmail contracts on February 9, 1934. On the same day, President

Franklin Roosevelt ordered the Army to provide airmail service. For

several months, from February 19 to June 1, 1934, the Army flew

the mail. Unfortunately, the Army had inadequate equipment and

took over during a particularly severe winter, leading to dozens of

crashes and 12 pilots killed.

Airmail routes were reorganized and new contracts were signed

with domestic carriers beginning in April 1934. In 1941, the United

States Court of Claims found that there had been no fraud in how

airmail contracts were awarded in 1930. Because he structured

contracts to encourage the production of larger aircraft capable of

carrying more passengers, Brown is often credited with spurring the

development of the modern airline industry.

International Airmail

Airplanes were used to transport mail internationally with the

establishment of routes from Seattle to Victoria, British Columbia,

on October 15, 1920, and from Key West, Florida, to Havana,

Cuba, beginning November 1, 1920. The Havana route was

discontinued in 1923, but resumed on October 19, 1927, marking

the beginning of regularly scheduled international airmail service.

Congress authorized the Postmaster General to enter into long-

term contracts for flying the mail internationally on March 8, 1928.

On October 1, 1928, Foreign Air Mail (FAM) Route 1 began regular

service between New York and Montreal. In 1929, routes were

Charles Lindbergh, 1926

Before Charles Lindbergh made his record-breaking solo

transatlantic flight in 1927, he flew the mail. Lindbergh

was the chief pilot for the Robertson Aircraft Corporation,

which held the contract to provide airmail service

between Chicago and St. Louis beginning April 15, 1926.

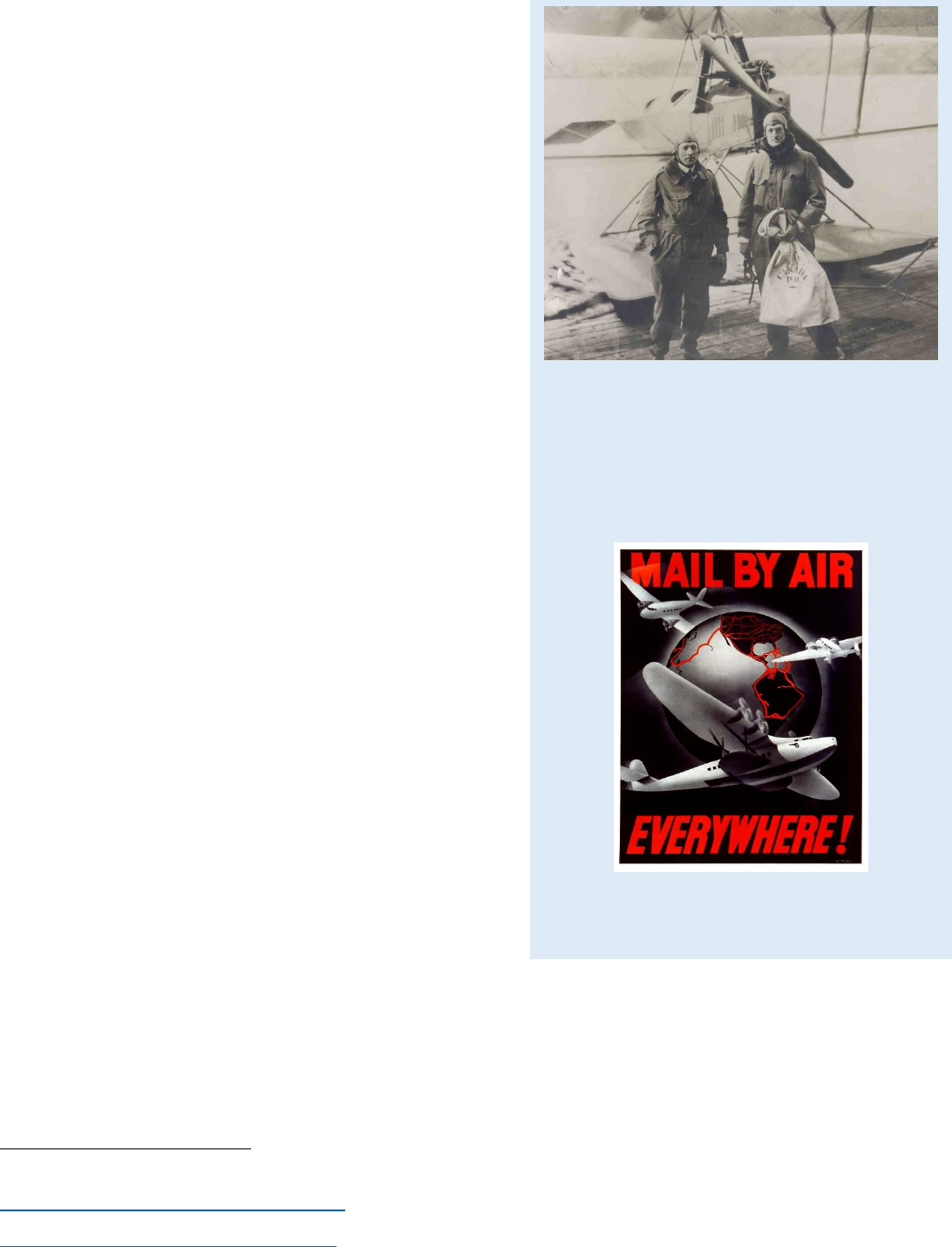

Weighing airmail in Los Angeles, 1926

Los Angeles Postmaster Patrick O’Brien weighs mail for

dispatch on April 17, 1926, the first day of service on the

Los Angeles–Salt Lake City contract airmail route. From

1926 to 1930, airmail carriers were paid on a weight

basis.

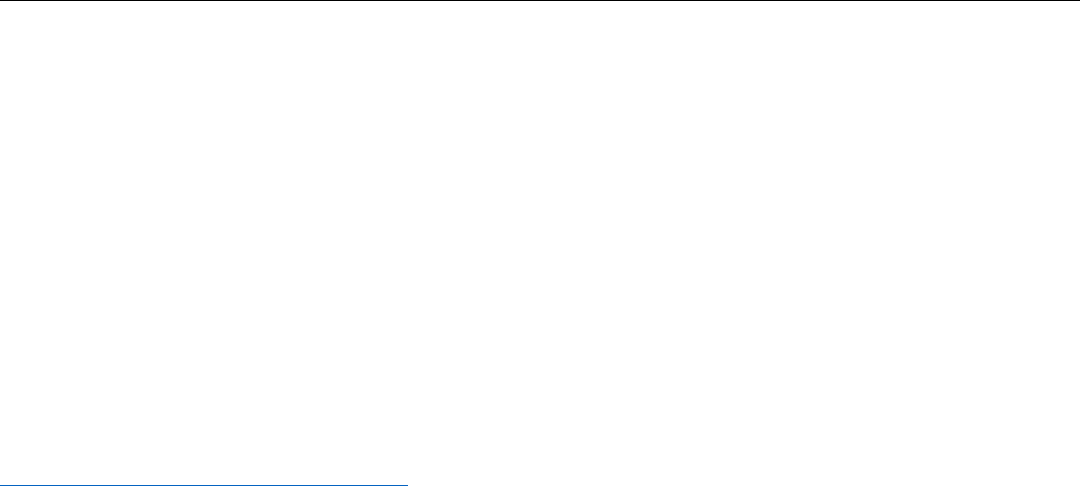

Loading airmail, 1930

Bags of mail are loaded into a Ford Tri-Motor Mail

Passenger Plane. Ford hoped its all-metal “Tin Goose”

would attract passengers — it could carry 15 people as

well as the mail. Until passenger traffic picked up in the

late 1930s, airlines depended on mail transportation

contracts for survival.

6

established from Miami to Nassau, Bahamas, on January 2; to

San Juan, Puerto Rico, on January 9; to San Cristobal, Canal

Zone, on February 4; and from Brownsville, Texas, to Mexico City

on March 10. By the end of 1930, the United States was linked by

air with nearly all the countries in the Western Hemisphere.

Transpacific airmail routes began operating on November 22,

1935, with FAM Route 14, from San Francisco via Hawaii,

Midway, Wake, and Guam to the Philippines. Airmail service was

extended to Hong Kong on April 21, 1937; to New Zealand on July

12, 1940; to Singapore on May 3, 1941; to Australia on January

28, 1947; and to China on July 15, 1947.

Transatlantic airmail routes connected the United States with

Europe beginning May 20, 1939, with the 29-hour flight of Pan

American Airways’ Yankee Clipper from New York to Marseilles,

France, via Bermuda, the Azores, and Portugal. That same year,

on June 24, a route was inaugurated between New York and

Great Britain by way of Newfoundland, Greenland, and Iceland.

On December 6, 1941, direct airmail service to Africa was made

possible by the inauguration of a route from Miami via Rio de

Janeiro to the Belgian Congo. Though interrupted during WWII,

improvements in aviation fostered the rapid expansion of

international airmail routes in the postwar years.

On October 4, 1958, a jet airliner was used to transport mail

between London and New York for the first time, cutting the

transatlantic trip from 14 hours to 8.

End of an Era

Airmail as a separate class of domestic mail officially ended on

May 1, 1977, although in practice it ended in October 1975, when

the Postal Service announced that First-Class postage — which

was three cents cheaper — would buy the same or better level of

service. By then, transportation patterns had changed, and most

First-Class letters were already zipping cross-country via airplane.

Airmail as a separate class of international mail ended on May 14,

2007, when rates for the international transportation of mail by

surface methods were eliminated.

HISTORIAN

UNITED STATES POSTAL SERVICE

MARCH 2018

1

Benjamin B. Lipsner, The Airmail: Jennies to Jets (Chicago: Wilcox & Follett Company, 1951), 83–84.

2

“Airmail’s Odyssey: Inauguration to Golden Anniversary,” Postal Life, May-June 1968, 10, in HathiTrust at

https://hdl.handle.net/2027/uiug.30112106587246 (accessed February 9, 2018).

3

“Practical Hints on Flying,” Air Service Journal, January 10, 1918, 33, in HathiTrust at

https://hdl.handle.net/2027/njp.32101048919383 (accessed February 9, 2018).

4

Quoted in Congressional Record, May 6, 1918, 6098.

First International Mail Flight, 1919

Eddie Hubbard (left) and William Boeing stand in front of

a Boeing C-700 seaplane near Seattle after returning

from a survey flight to Vancouver, British Columbia, on

March 3, 1919. They brought with them a pouch with 60

letters, making this the first U.S. international mail flight.

In 1920, Hubbard began flying the first international

contract mail route, from Seattle to Victoria, British

Columbia.

Airmail poster, 1938

In 1938, airmail routes sped up mail delivery to Canada,

Central and South America, the Caribbean, and parts of

Asia.

7

5

Ibid.

6

The Baltimore Sun, November 10, 1910, 16.

7

The first authorized U.S. Mail flights in 1911 were preceded by an unauthorized U.S. Mail flight in 1859, and a flight that was

authorized in November 1910 but never took place.

On August 17, 1859, balloonist John Wise transported the first U.S. Mail by air, with the cooperation of local postal employees, but

without authorization from the Postmaster General. Wise departed from Lafayette, Indiana, with more than 100 letters, hoping to reach

Philadelphia or New York City, but a lack of wind ended the trip just 30 miles later. Upon landing, Wise transferred the mailbag to a

railway postal agent, who put it aboard a train to New York.

Postmaster General Hitchcock authorized the carriage of mail by an airplane to New York City, from the deck of a steamship Kaiserin

Auguste Victoria when it was 50 miles offshore. The flight, scheduled for November 5, 1910, was cancelled due to stormy weather. Had

it occurred, it would have been not only the first authorized U.S. Mail flight, but also the first take-off from the deck of a ship.

8

In his annual report to Postmaster General Hitchcock dated November 29, 1911, Second Assistant Postmaster General Joseph

Stewart, who was in charge of mail transportation, recommended the appropriation of $50,000 for “an experimental aerial mail service”

in view of “the rapid development of the aeroplane” (Annual Report of the Postmaster General, 1911, 145). It’s unclear if his request

was passed on to Congress; it apparently wasn’t considered until 1912.

9

39 Stat. 1064, March 3, 1917.

10

Annual Report of the Postmaster General, 1923, 8.

11

Details of the lighting equipment are discussed in Aircraft Year Book, 1924 (New York, NY: Aeronautical Chamber of Commerce of

America, Inc., 1924), 42–43.

12

Quoted in The Roll Call: Air Mail Pioneers, second edition (n.p.: Air Mail Pioneers, 1956), 43.

13

Statement of Postmaster General Harry S. New, September 23, 1925, in Aircraft: Hearings before the President’s Aircraft Board,

volume 1 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1925), 265, in HathiTrust at

https://hdl.handle.net/2027/umn.31951d035053734 (accessed December 5, 2017).

14

45 Stat. 594, May 17, 1928. The Air Mail Act of February 2, 1925 (43 Stat. 805), had limited carriers’ compensation to 80 percent of

the revenue attributed to the airmail they carried. This was a money-losing formula; few bids were received. The act was amended on

June 3, 1926 (44 Stat. 692), allowing carriers more compensation, figured on a weight basis. Even then, few contractors profited due to

high operating costs.

15

46 Stat. 259, April 29, 1930. Among its other provisions, the Airmail Act of 1930 authorized the Postmaster General to require carriers

to offer and/or increase passenger service, and allowed him to consolidate and extend airmail routes.